Interviewing Performing Artists

…and others: A Practical Guide

This collection originated with the session, “Interviewing Performing Artists” at the 2008 Association of Music Personnel in Public Radio Conference in Mobile, Alabama. We are indebted to these colleagues who were so generous with their time, thoughts and experience — published here, with permission, for the Transom Online Workshop. —David Srebnik and Cynthia May (of Virtuoso Voices)

Contributors

- Bob Edwards (Host, Sirius-XM The Bob Edwards Show)

- Susan Stamberg (Special Correspondent, NPR )

- Robert Siegel (Host, NPR All Things Considered)

- David Brown (Host, KUT-Austin Texas Music Matters; former Host, APM Marketplace)

- Wally Faas (Host, WQLN-Erie PA)

- Lisa Mullins (Host, PRI The World)

- John Diliberto (Host, Echoes)

- Jim DeRogatis (Co-Host, APM/WBEZ Sound Opinions)

- Greg Kot ((Co-Host, APM/WBEZ Sound Opinions)

- Peter Sagal (Host, Wait Wait… Don’t Tell Me)

- Kurt Andersen (Host, PRI/WNYC Studio 360)

- Neal Conan (Host, NPR Talk of the Nation)

- Lynn Neary (Correspondent, NPR)

- Brian Newhouse (Host, APM Symphonycast)

- Marco Werman (Host, PRI The World)

- Kai Ryssdal (Host, APM Marketplace)

- Aaron Henkin (Producer/Host, WYPR-Baltimore MD The Signal)

- Faith Salie (Host/Interviewer, The Sundance Channel)

- Paul Ingles (Producer and NPR Liaison to Independent Producers)

- Judith Krummeck (Host, WBJC-Baltimore MD)

- Michael Krall (Program Director, WBHM-Birmingham AL)

- Boyce Lancaster (Host/Producer, WOSU-Columbus OH)

- David Schulman (Producer, Musicians in Their Own Words)

- Julia Figueras (Host/Producer, WXXI-Rochester NY)

- Martin Perlich (Author, The Art of the Interview)

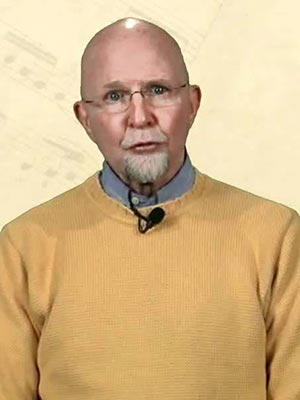

Bob Edwards (Host, Sirius-XM The Bob Edwards Show)

- Be warm and welcoming. Unless you really HATE the artist’s work, say something positive about the book, cd, whatever — even the biggest stars like compliments. This is more than good manners — it helps to relax the guest. A relaxed guest will be more forthcoming than a nervous, uptight guest who figures you’re going to ask about that DUI, the rehab or the lawsuit by the ex.

- Think of it as a conversation and not an interview. If you do an interview, it will likely SOUND like an interview. How do you talk to a friend over a beer? First you LISTEN — and you react to what you’ve heard. If someone tells me something really interesting, I’ll simply say, “Really?” or “No!” Those are little words of encouragement that signal the speaker to continue — and to expand on previous remarks. If your guest is truly confusing, try “Huh?” Works for me.

- Try to have an arc to the interview — a continuum that follows an orderly path through a life, a career, a project. Another option is to divide it into sections: Art, personal stuff, pet causes or community service. Make it easy for your listener to follow the story.

- Don’t trust the web. Errors last forever in cyberspace. (I love reading quotes attributed to me that I never said. Whoever wrote my Wikipedia entry got my date of birth wrong and said I home-schooled all my kids. At least I’m allowed to edit THAT one.) If something you find seems outrageous, it could be for a reason. Try saying, “It’s not really true that you make stew from roadkill, right?”

- Indulge yourself. Ask the question you’ve always wanted to ask. “What’s that lyric about?” “What inspired that painting?” “That’s such a sad song — did your dog die on the day you wrote that?” But then you have to be prepared if the guest says, “Yes he did, and I still miss him terribly.”

Bob Edwards interviews eastern Kentuckians about their “Exploding Heritage”:

Susan Stamberg (Special Correspondent, NPR)

Listening to answers is more important than asking the question.

Best question is often the simplest: WHY?

Prepare in advance as if your life depended on it.

Think, in advance, of what you want to get out of the interview.

Think of the beginning, middle and end of the interview — make your questions related, not random.

Susan Stamberg presents some of her favorite interviews, The Stamberg Files: Essays, Audio-tours, and Interviews, Hearing Voices from NPR:

Robert Siegel (Host, NPR All Things Considered)

Listen to what the person you’re interviewing says. She may answer one of your other questions.

And make it unnecessary. More important, he may say something much more interesting than you had anticipated, something worth dwelling on for a couple of questions.

Be prepared to dump the questions you walked in with if the conversation develops in an interesting way.

Arm yourself with quotations about the interviewee. You can put outrageous statements to him/her, provided they’re attributed to someone else.

Robert Siegel interviews musician “Richie Havens Face to Face”:

David Brown (Host, KUT Texas Music Matters; fmr. APM Marketplace)

Interviewing performing artists (musicians):

In reporting on popular music, I’ve found that there are essentially three ‘varieties’: a) the up-and-comer who’s genuinely grateful for your attention and is eager to be ‘led along’ by the interviewer; b) the second-tier ‘almost famous’ who’s more critically acclaimed than commercially successful and has already received a certain amount of buzz, and c) the commercially successful and/or established artist. There are exceptions, of course — but I think the interviewer approaches each ‘category’ somewhat differently.

They all start with certain tenets of good interviewing.

Prepare more than you think you’ll need to.

Have on standby short questions but don’t use them as a script.

Always remember your subject is more interesting than you are as a host.

Think in advance about the interview having a beginning–a middle–and an end. Don’t try to fake curiosity; be interested in your guest… and a similar rule:

Remember that “listening is an act of love”; care about your guest and it will be an awesome interview.

Now the ‘special considerations’ by category:

A’s: Unless well schooled in PR, the artist may well need your help to be put at ease. If taping, assure the guest that this is editable. Talk a little in advance before you’re ‘on’, and casually (but never insincerely) flatter them and their music. You, the interviewer, will probably have to frame the ‘what makes them special’ in your lede. The interview can be a great place for the listener to meet the artist and make an initial personal connection. Subjects like family and home can be goldmines. If interviewing a band, focus on one musician (the leader) — otherwise, the nervousness of everyone else tends to make the interview dissolve into giggly small talk and useless chatter.

B’s: These are the hardest to get right. It isn’t unusual for B’s to wear sunglasses in the studio and radiate ‘rock star’ attitude, but this is usually just a mask for insecurity. Chat with the artist a few minutes before the interview gets ‘rolling’, and try to make a human connection (the travails of the road, the fans, hometown small talk, etc.). Not only does this ease the artist, often during this pre-interview you get a sense of what matters to them. Play off that. Don’t hesitate to ask the artist what he/she wants to talk about. Ask about the future: ‘How do they define success’? Biggest creative obstacles at the moment?

C’s: Generally these are pretty easy. C’s have often done a million interviews, and most feel they haven’t anything to ‘prove’, so you won’t usually get much attitude. The challenge here is to think in advance of a narrative arc for the interview — a ‘backstory’ or theme that will make your interview memorable. Sometimes, this can be a direct riff on the theme of an album and how it relates to current events, or a progression of work. Another approach is a ‘state of the art’ interview, where you give the artist a platform to talk about culture, the music industry, songwriting, innovation… sometimes these can even make news. Since C’s are already commodities on the cultural landscape, hearing what they have to say about other facets of life, from the political to the spiritual, can make for compelling listening, while subtly providing insight on the artist’s music.

Disclaimer: I’m always trying to get better, and I’m constantly listening to the pros in hopes that something smart will rub off on me. So if you ask me about these tips a few weeks from now, my earnest hope is that I will have advanced enough to plausibly deny I ever wrote this…

David Brown interviews musician Latasha Lee:

Wally Faas (Host/Producer, WQLN-Erie PA)

Seven Tips

I’m not a professional interviewer. I only play one on the radio about once a month in what I call “Lobby Performances” because they’re live broadcasts of performances by, and interviews with, artists in WQLN’s lobby, which is large enough to accommodate a live audience of up to 80 or so.

Listening to recordings of these interviews has taught me a few things including:

- Get them started and get out of their way. Avoid interjectingf reactions like, “No kidding!” “I didn’t know that,” “Hmmmm,” “Wow”. When I used to do that, it was my natural reaction as a partner in a conversation. But, as a listener, I found them distracting. Laughing at their jokes is the one exception.

- Learn your questions. Prepare questions and have them in front of you, but be familiar enough with them that you can ask them as they relate to subjects the guest brings up, rather than binding yourself to your ordered list.

- Don’t tip your hand. I used to go over my questions with the guest before the interview, but no more because I learned that both of us feel more natural and have more fun when the questions are fresh. Before the interview, I do ask the guest if any subject is off limits.

- You’re not as interesting as they are. So keep them in the spotlight by making questions brief and focused, and by sharing concise opinions and stories (or better yet, keep those to yourself).

- No genuflecting. As much as you may admire your guest, resist gushing over them. Let the facts about their success speak for you (critical reviews, awards, CD sales, etc.). If you have the luxury of a live audience, its applause and hoots and hollers say more then you could say. Too much praise from you sounds patronizing and blunts your ability to ask challenging questions.

- Have fun. Your guest wants to present a friendly face to your audience, so be a good host and spend a little time with them before you go on; take care of anything he or she needs and allow time for small talk and getting comfortable with each other. Laugh at their jokes.

Feedback is a good thing. Ask audience members (live and radio) what they liked and didn’t like. Listen to recordings of your interviews.

Lisa Mullins (Host, PRI The World)

The Interview

Here are a few suggestions particularly aimed at interviewing performers. They are not listed in any order of importance.

- Try not to think of the interview as a free-flowing chat. Take your role as interviewer seriously — meaning do your homework and write your questions down. There are so many directions a music interview can take that it can easily become unwieldy. That’s why it helps to streamline your questions and have a beginning and an endpoint in mind. Your interview will benefit from having structure — both in preparation and in execution. Don’t worry — there will be plenty of room for creativity and improv within that framework.

- Be sure you’ve listened to the artist’s latest work prior to the interview — preferably more than once — until you can comfortably refer to a few particular tracks or solos or other noteworthy elements.

- During the interview, get the musician to demonstrate a particular technique on his or her musical instrument — voice included — if at all possible. Prior to the interview, ask if the guest is comfortable with this. Some will shy away; some will jump at the chance.

- If you need to tread on well-worn territory or an oft-told experience of the artist, try to do it in such a way that it gives the subject matter new meaning — think this through beforehand. The idea is to keep the artist from naturally reverting to autopilot.

- Keep the spotlight on the artist’s expertise, not your own — at least while the mic’s on.

- Even the most accomplished musician doesn’t necessarily make a strong interviewee. But one thing musicians love to talk about is the music itself. Keep this in mind if your broader questions are falling flat.

- Avoid what can admittedly be considerable temptation to fawn. Putting the artist at ease is good — but even if you’re president of the fan club, remind yourself that you’re the listeners’ proxy.

- Be respectful of the musician’s time limits, particularly if he or she is on tour and likely tired. This is easy to forget when the conversation is flowing.

- If time allows, ask the guest if there’s any point he or she would like to make. For live-to-air interviews, you may want to pose the question before the mics are on. For taped interviews, you can ask this as a closing question. It often elicits a meaningful articulate response.

Lisa Mullins at the “Goth Service: St. Edward, Cambridge, UK (w/ Leonard Cohen’s Music)”:

John Diliberto (Echoes)

Five Simple Scenarios For Interviewing a Musician

- Have a purpose for your interview. If the only reason you’re interviewing is to hype the local concert or meet the celebrity, then maybe you shouldn’t be doing this interview. Your listeners won’t care that you got to hobnob with a star and if you can’t create a compelling reason why this artist is worthy of attention, then just don’t bother. Listeners want content not hype.

- Listen to the music. I don’t know how many interviews I’ve done that started with the artist asking, quite innocently, “Have you heard the record?” That tells me they do a lot of interviews where the interviewer, indeed, hasn’t listened. I feel like I spend the first 15 minutes of an interview breaking down an artist’s preconceptions from the previous, ill-informed interviews to which they’ve been subjected.

- Don’t be afraid to ask the hard question. They aren’t your friends and you don’t have to worry that they won’t like you or walk out. Although occasionally they do.

- Don’t be afraid to ask the obvious question. I got this from listening to Terry Gross, who, besides being a probing interviewer, also knows where the good stories are and isn’t afraid to query into known terrain, because a good story is still a good story, even if it’s been heard before. Chances are, most people still don’t know it. Then find a different angle on that story.

- Research. With the Internet, there’s not only no excuse not to research your subject, it’s unconscionable not to. If you want to get a musician in your pocket, find out something deeply obscure from their past that might be buried in that fanzine interview they did 20 years ago, like that Elvis cover band the classical cellist used to play in. Or find out what their real passion is in a project. Even if it’s not interesting to you, they’ll think you “get it.” Then you can ask whatever you really want. When the musician thinks you know more about them than they do, they’ll take you more seriously. It also can open up a whole different line of questioning.

John Diliberto interview for musician “Brian Eno’s 60th Birthday”:

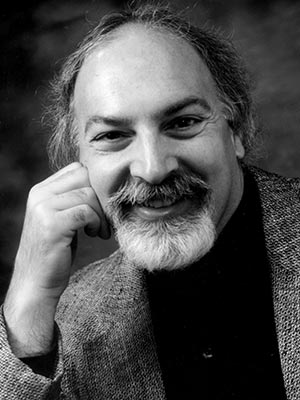

Jim DeRogatis (Co-Host, APM/WBEZ Sound Opinions)

Interview Chops… Some Comments

Rock critics and music geeks love lists (see: Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity), so let me put in list form the knowledge I’ve synthesized during 26 years of interviewing. (My first interview: the great rock critic Lester Bangs, when I was a 17-year-old senior at Hudson Catholic Regional High School for Boys in 1982. One of the last who was a “big deal” music celebrity with a name that you might recognize: Hannah Montana/Miley Cyrus. Regardless of what that juxtaposition suggests, it has not been all downhill since.)

- Prepare exhaustively. Read everything you can get your hands on about the person you’re about to talk to: new stuff, old stuff, ancient history, the phone book in their area code. And then throw it all away!

- You need to have that background on file in your brain, so you can reference it at a moment’s notice if the subject gives you an opening. (“Funny you should say that, because I read that as a kid, your hobby was breeding goats, isn’t that right?”) But above all, you want to have a conversation! You know, just like the person across from you is a normal human being, even though he or she almost certainly is not. (If they were, why would you be interviewing them? And human nature being what it is, even the person in the street is probably way more complicated and unrepresentative of “normal,” whatever that may be, then you might assume at first.)

- Whatever you do, do not compile a list of “great questions” and then ask them in order, one to ten. Have a few questions ready as emergency fallbacks, but listen to what your subject is saying. Be flexible enough to go in the directions that he or she is taking you. Unless…

- They’re one of those subjects who just want to sell-sell-sell you. Some interviewees, particularly celebrities on the road with new product to hawk, do not listen to your questions; they simply hit “play” on the tape recorders inside their pea brains. You may ask, “How was the weather in Cannes last week?” and they may answer, “My new album is available in stores now, and the movie opens next week!” So be ready to derail the hype express if warranted. As long as you’re heeding point three above, don’t be afraid to jump in with an aggressive or digressive question. Get in their faces if you have to, as we used to say in Jersey.

- In case the importance of point three hasn’t become clear as yet, let me say it again: Listen. Listen, listen, listen, listen. LISTEN!

- And, finally, despite the empathy of all that listening, remember that you are not there to have this person like you. Be respectful or congenial, yes. But do not (do not, do not) kiss ass. Do not try to impress. Do not make the mistake of thinking your subject likes you or is a real person just like you! (See point two again.) You are trying to get at some small sliver of the truth, and to expose some possibly hitherto unseen aspect of the subject’s personality, philosophy, or life’s work. As Lester Bangs (Phillip Seymour Hoffman) says to the young Cameron Crowe (Patrick Fugit) in the director’s autobiographical film, “Almost Famous”: “You can’t make friends with rock stars. These people are not your friends!” Substitute “rock stars” for “interview subjects” in any situation — actor, Nobel Prize winner, congresswoman, revolutionary, cartoon character, or America’s Next Top Model — and you will never, ever go wrong.

Jim DeRogatis interviews movie critic Roger Ebert:

Greg Kot (Co-Host, APM/WBEZ Sound Opinions)

Interview Tips

- Prepare ahead of time, and know your subject. Avoid the questions that have been asked a million times, and look for the kernel of information in your research that can lead you to a revelatory interview rather than a perfunctory one. In your notes, use a flash-card approach with certain key words that will prompt a line of questioning; then phrase the question in your own words in the moment while looking the interviewee in the eye.

- Rather than an interview, think of it as a conversation.

- Listen to the interviewee’s answer, and follow-up. The initial response rarely produces any new information. But following up the initial question is where the real gold is. Keep asking for more detail: What did that feel like? Why? How did you do that exactly?

- Don’t start with your toughest, most provocative questions. Build up to them after developing a bit of rapport with the interviewee. Look for openings in the conversation that allow you to work in those tough questions. “Since you brought up X, were you surprised at how much of a controversy it became?”

- Just about any question is OK to ask, if you phrase it in the right way. When bringing up delicate subjects, don’t make it confrontational or personal. But a hint of empathy in the way the question is phrased can often elicit a more personal response. “The public/the media/the industry perceives what happened this way… What was going through your mind when you read/saw/heard about that.”

- Don’t let go if the response is evasive or unsatisfactory. That’s when you can start digging a little harder. “Really? People would find that answer disingenuous/hard to believe/incomprehensible. The evidence brought up by X suggests exactly the opposite.” Again, you’re being confrontational without making it personal.

- Do not interrupt the answer. Let the person finish, and then pause a few ticks more before following up, especially if you’re dealing with a sensitive subject. The pregnant pause can be your friend. In a live interview it can be awkward, and often the interviewer rushes to fill in the dead space and then quickly changes the subject, which lets the interviewee off the hook. It’s worth it to wait it out more often than not. Remember, not all interviewees will be as skilled with words as the interviewer, and they sometimes need time to formulate answers, or to think of what they want to say. Don’t rush them, and above all don’t talk over them. The words you stomp over could prove valuable and lead right into your next question.

Greg Kot interviews author Simon Warner:

Peter Sagal (Host, Wait Wait… Don’t Tell Me)

Interviewing Musicians

I don’t think of myself as an interviewer of musicians… but I do interviews (in the context of our “Not My Job” game) and thanks to our excellent bookers, we’ve had a good selection of musicians on the show, especially in the last few years. We’ve talked with Branford Marsalis, Nancy Griffith, Yo-Yo Ma, Melissa Etheridge, John Mellancamp, Herbie Hancock, Corky Siegel, John Pizzarelli, and of course, Weird Al Yankovic. If I have any particular advantages as I’ve talked to these and other artists, they would be these:

- I’m almost entirely ignorant of music. I have a tin ear, and no particular expertise beyond that of a casual fan. Which means that I never start a question with the phrase, “So, on your fourth album, you replaced your long-time keyboardist with a well-known session player…” While interesting to the musician, and perhaps flattering as well (which I think may be the point of asking a question like that), this kind of granular inquiry is alienating to the listener who, statistics indicate, is as uninformed as I am.

- I was once a playwright, meaning that I, too, once sat in a room, trying to come up with something new, and then had to go sell what I created to a perhaps unwilling public. While there are a lot of differences between music and theater, particularly commercially, that at least gives me a starting place with musicians. How do they decide what to do next? How sensitive are they to critical response? How much of a responsibility do they feel to their audience, versus to their own creative impulse? How much pressure to they put on themselves to do something new? How do they deal with the ever-present tension between business and art?

- I host a comedy show. Nobody expects us to conduct a “serious” interview, so we don’t have to… we can ask goofy questions in the hope of getting an equally goofy response. Thus, for example, instead of asking Melissa Etheridge about the politics of global warming, I can ask her how hard it was to find a rhyme for the phrase “Inconvenient Truth.” Most times, the musician not only responds in kind, but takes an audible pleasure in being allowed to be silly, or even provocative, and says things he or she wouldn’t say in more serious interviews. For example, we asked a series of musical guests their opinion on what is the sexiest instrument. Unsurprisingly, Weird Al thought it was the accordion.

Peter Sagal interviews “Comedian Tig Notaro, Playing Not My Job”:

Kurt Andersen (Host, PRI/WNYC Studio 360)

If possible, combine an interview with some performance. Experiencing the performer doing what they do in real-time can provide great fodder, specific and nuanced, for further conversation. If you respond positively — sincerely — to what they do, your pleasure will both be infectious to listeners and increase your rapport with the performer. And performance is also something radio can do that print can’t.

Know (or seem to know) a little more than the interviewee expects about them and their field. They will respond positively to your non-ignorance. This is a matter of research, of course. Or of colleagues in the control room feeding you key facts: I am a jazz and hip-hop ignoramus, for instance, but when I was interviewing Herbie Hancock and Taleb Kwali recently, and they each made passing references to other musicians of whom I knew nothing, a couple of quick, unsolicited IM’d IDs from a producer made me seem smarter, which in turn made each of them more voluble and friendly as talkers.

On the other hand, don’t be afraid to ask stupid questions. If you don’t understand something someone has said — an arcane reference, an opaque personal matter — follow up and ask what they mean. It’s better to look a little dumb yourself than to make listeners feel dumb or confused.

Try not to embed answers in your questions. This is hard, and I fail at it regularly. But instead of asking, say, “Do you still get scared before you go on stage or at this point are butterflies a thing of the past?” ask, “How do you feel just before you go on stage.” That kind of indeterminacy increases the possibility of a surprising or subtler or truer answer.

Always try to ask some question(s) you think they’ve not been asked before. In some cases, with performers who’ve done a million interviews, this will prove impossible. And I don’t mean questions of the “If you could be a fruit, what fruit would you be?” variety. But at least endeavoring to push them off-script and break them out of their spiel of canned answers is a valuable goal.

Don’t necessarily leave the “tough” questions to the end. Journalists of every kind always tend to do this in interviews, of course — you don’t want the interviewee cranky and guarded at the beginning, and for many of us, who are weenies, we want the potentially uncomfortable part of the interview to be as brief as possible. But the right kind of difficult question can pay off in good radio in unpredictable ways, more than enough over the long haul to justify one’s own discomfort.

Kurt Andersen interviews architect Pico Iyer:

Neal Conan (Host, NPR Talk of the Nation)

- Only ask one question at a time… ask two, and they’ll just answer the one they like.

- Come prepared with questions, but LISTEN to the guest, who will often tell you what the next question should be.

- Try to structure your interview so it has a beginning, a middle and an end.

- Preparation, preparation, preparation.

- There is a difference between live and taped interviews, and between host interviews and reporter interviews… Live/host: always start with the most interesting question, while a taped reporter interview can often begin with a “waist high fastball” to allow the guest to deliver the message he/she wants, THEN get to the interesting stuff.

Neal Conan replays an “Interview That Made Us Blush” (TOTN Memories), “Sudden Paralysis and ‘The Best Seat in the House'”:

Lynn Neary (Correspondent, NPR)

- The key to a good interview is listening.

- Don’t be afraid to ask a dumb question… sometimes they yield the best answers… but be careful with this one, you don’t want your guest to think you are not too bright or ill prepared… maybe just a little “naive”. I think Terry Gross is a master at this. You know she walks into an interview better prepared than anyone and then asks one of these disarming little questions that just makes a guest open up.

- Which of course, brings us to preparation. I used to have a quote above my desk: “Chance favors only the prepared mind” or something like that, from Louis Pasteur, I believe. You need to know a lot about the guest and then act like you don’t know that much and then, when you hear something new, be ready to jump on it.

- Listen (did I say that already?)… here is another way of putting it… the interview is not about you, it is about the guest.

- Bring real curiosity to the table… there is no substitute.

Lynne Neary interviews musician David Byrne:

Brian Newhouse (Host, APM Symphonycast)

Some tips I’ve learned (often the hard way) about interviewing

I believe passionately that one of the first and most important things is for the interviewer to ask him/herself: am I genuinely curious about my guest and what he/she does? Even more basic than that, do you feel that you have, in general, a vivid sense of curiosity at all? If not, you may be in the wrong line of work. If so, what follows are just a few tips on manifesting that sense of curiosity.

- The Importance of Story. Try to elicit a story that really engages the guest, i.e. “tell me a scary story from your early career, a time when you were frightened spitless.” Pianist William Wolfram tells this fantastic black-humor story of trying to calm himself before his first performance of the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1; he drank so much coffee that he got a terrible case of the shakes… “which wasn’t such a bad thing because of those fast octaves (cue the music) that I had to play….” This was a funny, revealing moment.

- Ask for a Childhood Memory. The idea, again, is to bring the guest to tell a great, memorable story. For instance, Edo de Waart came to conduct the Minnesota Orchestra in a piece by his Dutch countryman Rudolf Escher, written in the early 1940s. Edo was a toddler during WWII and I asked him to take me back to his own memories of Amsterdam during the war and put those memories together with this piece by Escher. What followed was a passionate re-telling of his earliest memories of hunger, when his family ate tulip bulbs to survive; of being lifted onto a Canadian tank by his father… all this was a powerful set-up to the Escher piece we heard in the concert.

- Admit Your Ignorance. If I reveal that I don’t know everything, and I invite the guest to tell me even some basic fact, or to correct me when I’m wrong, it can be a very human moment and it allows the listener into the conversation in a fresh way. This happened once with Leonard Slatkin, who was conducting Copland’s ballet Billy the Kid. Leonard was describing the action of the ballet and especially the gunfight. I always thought that that was the part where Billy got killed, and said so, and Leonard corrected me. This interchange elicited a rare complimentary email from a senior manager at MPR, citing the fact that this interchange invited the listener in; by not making myself the expert, by showing my error.

- Always, Always, Always Keep the Listener In Mind: Let Him/Her Have Your Seat. Admit your own native curiosity, your own passion for the guest’s work. I once gushed to violinist Vadim Repin that I couldn’t believe what he did in a Paganini recording I’d recently heard; it sounded as if he had over-dubbed an exceptionally difficult part with another violin; I asked him if he could do it for me live with his fiddle right there and then, just to make sure the recording wasn’t over-dubbed. He was flattered, challenged, and he laughed and said that I’d hit him below the belt with that question, but he’d try. He did beautifully; not as good as the commercial CD, but this resulted in a humane fun moment… sparked by my own amazement and curiosity.

- Do Your Research. Not much to say about this Interviewing 101 tip. Surprise the guest by showing him/her that you’re prepared.

- Tricks of the Trade. I love these questions, and they almost always yield good tape:

- Hold a mirror up to what it is you do for a living. Tell me what you see.

- Why do you do what you do?

- What is new in your life and work; describe the green, growing edge of what it is you do. (Note: Don’t edit out that thoughtful pause you’ll almost invariably get afterward. I love ‘hearing’ the guest think, really think.)

Brian Newhouse interviews musician Stephen Hough:

Marco Werman (Host, PRI The World)

Art of the Interview

- Do your homework: Know about the person you’re speaking with and how they speak. Musicians can be great practitioners of their art, but notoriously bad at speaking about it. Know ahead of time whether they’re likely to deliver yes or no answers, and plan accordingly.

- Ask how music affects them as artists and humans.

- Don’t lead by asking them about their own music. First, ask them about their lives.

- Don’t count on cliché questions: use those as a warm up and as background. If there are real surprises you can use the answers front and center: How’d you get the name of your band? What are your chief influences? What is the meaning of that song? These are all potentially useful questions, but I find that the answers rarely provide anything terribly interesting. Still, don’t forget to ask.

- Ask them about where they come from. What affect did growing up in X have on the way you sound today? It helps to set the context, get some personal anecdotes, and find out what motivates them.

Marco Werman interviews Mali musician Khaira Arby:

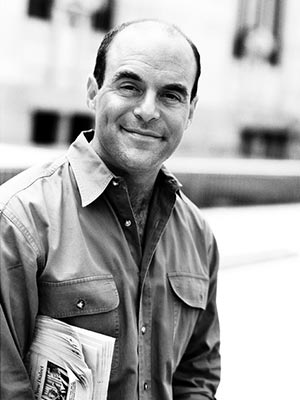

Kai Ryssdal (Host, APM Marketplace)

Rule number one for me is preparation. Know everything you can — or everything you have time to study — about what or who the subject of the interview is. From there everything just sort of happens, and it lets rule number two kick in. Especially on a show like ours, personality is so important. So I guess I would say rule number two is let a bit of yourself come through. (And of course you can’t really do that unless you really know what you’re talking about.)

Finally, I think the warm-up is under-rated. Whether it’s in person or in the studio on an ISDN, spending even a little time chatting with the interviewee beforehand can really pay off. It sets them at ease and it lets them get a glimpse of you as a person before they have to interact with you ‘professionally.’

Kai Ryssdal interviews President Obama:

Aaron Henkin (Producer/Host, WYPR-Baltimore MD The Signal)

- Your ultimate allegiance is to your listeners. You’re their ears and their mouths during an interview. Ask questions that respect and reward their curiosity and you’ve done your job.

- People tend to put performers and artists on pedestals. Give your listeners a chance to learn about your interviewees’ vulnerabilities, self-doubts, and insecurities. Everybody has these feelings, everybody can relate to them, and they’re usually pretty fascinating to hear about.

- Think about the order of your questions as carefully as you think about the questions themselves. (For example, you probably don’t want to start by asking someone to talk about his or her self-doubts and insecurities.) The order of your questions should craft a narrative arc, and you can save yourself a lot of post-interview slicing and dicing if you spend some extra prep time beforehand.

- Don’t be afraid to react like a human being. Having a prepared list of questions is great (and essential), but you aren’t doing your listeners any favors if you’re busy looking at your next question instead of listening. If your interviewee tells you something that sounds like it must have been a totally surreal experience, simply say: “Wow, what a surreal experience that must’ve been…” Chances are an interesting moment of self-reflection will follow.

- I always like asking folks what they think they’d be doing if they weren’t doing their art, music, etc. The answers are usually either highly comical or highly revealing in an unexpected way.

Aaron Henkin interviews musician Wendel Patrick:

Faith Salie (Host/Interviewer, The Sundance Channel and PRI Fair Game)

The Art of Interviewing the Artist

Don’t Be Such A Girl

Even if you’re not one. Here’s a gender stereotype (a genderalization, if you will) of which I became aware when I first started interviewing: when women listen, they tend to give a lot of audible affirmations to the speaker. Acknowledgements such as “uh-huh,” “I know,” “mm-hmm,” “yes!” all serve to express, “I’m listening, and I’m with you.” And off air that’s a lovely impulse and conducive to conversation, but it turns out to be really distracting to listen to on the radio. Be judicious in giving voice to encouragement. Let your guests know you’re listening not by making “listening sounds” but by letting what they’re saying lead organically to your next question.

You’re Not That Fascinating

Well of course you are when you’re not conducting an interview. You know that, and I know that. But always remember the interview is not about you. (Isn’t that a shame?) In college we would roll our eyes at peers who asked “flex questions.” Those were the kind of questions that didn’t seek answers but rather sought to demonstrate the insight and acumen of the questioner. The simpler and more direct your question is, the richer the response you’ll most likely get. Sometimes a quiet and earnest “Why?” will lead to the most revealing answers. Surprisingly, that simple query knocks many guests off their game — which is a very good thing. So many artists are used to talking about what they do and what they think, but they’re rarely asked merely, “Why?”

Leave Yourself Some Breadcrumbs

While maintaining eye contact with your guest creates magical intimacy (if you’re lucky enough to be conducting the interview in person), never hesitate to put pen to paper to take very brief notes as you’re listening. If you hear something provocative, compelling, surprising, fecund — make a note of it so you can return to it later without interrupting the artist’s immediate flow. Breadcrumb notes are also a great way to wrap up an interview with levity: you can have a callback at the end of the interview to allude to and share a laugh over something he’s previously said. It makes the listener feel included and the artist feel like he’s really been heard.

Pray For Mistakes

They’re unscripted manna from Interview Heaven. When you stumble over a word, you’re human — and even sometimes an accidental humorist. When you ask a hackneyed question, call yourself on it (“I can’t believe I just asked you that — have you been asked that a million times?”). When you pronounce something wrong, ask your guest to correct you. If you’re about to sneeze, do it. Basically, be transparent. Transparency is so much more engaging than slick, detached, seeming infallibility. Your listener won’t know what’s coming next — that’s compelling. Your guest will feel like she’s talking to a real person and will trust you more.

Pretend It’s Bedtime

Remember when you were a kid and you were being tucked in at night? The best thing to say if you didn’t want your mom to leave you was, “Tell me a story.” When it comes down to it, we all just want to hear stories. Think of every artist as someone with a story (or a hundred stories). Craft your questions so we can learn where she came from, what she remembers, what happened to her, what was her nadir, her epiphanous moment. And get specifics. For example, rather than saying, “How do you feel about your ascent into success and celebrity?” ask, “Tell me about the craziest encounter you’ve ever had with a fan.” Don’t swaddle a question in sophistication if saying, “Tell me a story about that…” will do.

Silence is… Platinum

It’s better than golden. Resist the urge to fill the void. You’re not a hostess at a dinner party; you’re a midwife to a story. If you allow a moment to suspend (and this can feel like an eternity), you’ll often be amazed at what an artist will reveal.

Faith Salie interviews comedian Bobcat Goldthwait:

Paul Ingles (Producer and NPR Liaison to Independent Producers)

There are all kinds of interviews and some of the rules change for each setting. Interviews from which clips for a report will be drawn can unfold a bit differently than those that are done live, or that will be used as a studio Q & A. Some of what is written here applies better to one setting than another.

But the golden rule, as you will have read in almost anyone’s summary of interviewing tips, is TO LISTEN.

You HAVE to play the role of a member of your audience who is doing nothing BUT listening. They are not seeing or feeling anything that is going on in your head while you do the interview. Whatever else happening in the studio, or in the field, none of it — whether it has to do with how much time you have, what the recording device is doing, whether the guest is straying off topic, what your next question is — is of any concern to the listener. Which is why you have to FORCE yourself to listen harder because some part of your brain actually does have to manage that other chatter. But if you can’t learn to manage that chatter AND listen better, you won’t be doing your best work as a reporter.

Some Ideas on Managing that Chatter

Tell the guest what the finished product will be and ask them for concision. Some may disagree with me on this one but I think it’s OK to let a guest know what the ground rules are. If you are doing a pre-recorded studio interview for a talk show, and know ahead of time that your finished edited interview will run about 16 minutes, I think it’s perfectly OK to say to a guest:

“We’re going to talk for about a half-hour but the final segment will be about 16 minutes, so we’ll be editing this for time. Still, it’s to everyone’s advantage if you can be as concise as possible with the answers to my questions. Don’t try to give away the whole story in any answer. I’ll make my questions as specific as possible, and if you’ll keep answers focused on the topic in each question, that will work best. If I think we’re drifting off topic, is it OK if I interrupt you?”* (See below on interruptions.) Most will say, “Sure.”

I think the same strategy works for interviews you might be doing for a shorter report. Tell them it’s likely to be a 4:00 report and that you’ll be talking with other sources. So while you want them to answer naturally, I think it’s OK to ask them to stay concise. They may or may not comply but it works sometimes to ask. And it can relieve you from worrying about it so much as you go.

Be confident that you’re rolling. Whether you’re using an engineer in the studio, or rolling your own recording machine, well before the start of the interview, make sure that it’s working AND rolling out of pause before you start. Wear headphones. Check the meters once during the first answer, then try not to keep checking.

Study your questions and bring them on paper if you like, but don’t have them out as you interview. Again, I would tell my guest that, before we’re done, I might pull out my question list to see if there’s anything I forgot.

Again, I’ve never met a guest who didn’t understand that need. There’s no reason to feel awkward about it. If you set that up in the beginning, your brain will devote less energy to trying to imagine your question list, which distracts you from listening. That’s because you’ll have a chance to check it at the end — particularly if you ask the guest BEFORE YOU START.

It’s important to respect a guest’s time. If you say the interview will last 15 minutes, keep a very small part of your attention on when that time is about to expire. Say, “I want to be sensitive to your time here. I said 15 minutes and we’re about there now. Would you be willing to answer two more questions?” Set a reasonable extension. Most will say yes.

Preparation and Execution

Preparation is good but don’t leave your audience behind. Some interviewers won’t go into an interview unless they feel they know nearly as much as their guest about the topic. They’ve read their books; they’ve read other articles. They want to show off that they’ve done their homework and some of their questions may seem worded to impress the guest. I would never coach against preparation BUT, if you are so well prepared that your interview sounds like two colleagues at an academic conference, then you risk leaving your listener, who hasn’t done all the research, behind.

People tend to deride Larry King for his admission that he rarely reads the books of his guests because, he says, most of his listeners haven’t either. There’s something to that strategy but I also think it means that King misses the knowledge to steer the conversation to a useful place in the time he has. I’d recommend reading the book and doing the research but remembering in your questions that most of your listeners haven’t and shape them accordingly.

Try to adopt the uninformed listener’s mindset during the interview. Imagine a listener in their kitchen listening. Some of what they need to know to follow the conversation will come in an intro or in a finished story’s narration. You don’t need to give a listener a master’s degree on the subject in lengthy background lead-ups to questions.

Keep questions short. Get at values, feelings and motivation, as well as information. Radio is not as good at disseminating the facts as it is the feelings and emotions of the people involved in the issues. So find out how people involved feel about this trend or that trend. Why do they care? Getting at those root feelings can bring a story around to the common themes of human experience that listeners can relate to.

*Interrupting along the way. Again, if you say ahead of time that you might interrupt and get their permission, feel free to do so. If you know that a guest isn’t answering a question, it’s OK to hop in and say, “Excuse me… May I ask that question again, because I don’t think I understand?” (Better to say, you don’t understand, rather than suggest that they are straying off topic.) Ask again and make sure they know what you’re asking.

Interrupt and clarify. Again, think like a listener who knows virtually nothing about your topic. Be alert to jargon or something a guest is saying that wouldn’t be clear to a casual listener. If you are listening carefully, you’ll be ready with the “What does that mean?” “Explain what you mean by…?” And to get at values, feelings and motivation, be ready to hop in with “Why did you do that?” “How did THAT feel?” “What do you mean?” “Why is that important?”

Not happy with an answer? Ask again. Depending on how experienced your guest is at being interviewed, they may not do the best job of answering your question on a first pass as they, or you, would like. Be alert to an answer that isn’t clear to you. Just because you asked it and they answered it, doesn’t mean you have what a listener can understand later. So don’t miss the chance to say, “Let me ask you this again.” Some guests are a little intimidated by the dynamic of the interview and may relish the chance to be more clear. Now you have to be alert that you aren’t giving them a chance to change the substance of their answer; if it drifts significantly from an earlier answer, you can follow up again to clarify if the answers match up contextually. Again, if you are LISTENING.

Be open to the possibility of changing course. You will want to ask the questions you prepared or that your editor asked you to ask, but keep listening for something surprising that you didn’t think of ahead of time. You may steer briefly away from your mapped out course. You can always steer back.

Know the opposing point of view. Tim Russert often quoted one of his Meet The Press mentors, Lawrence Spivak, as saying, “Learn as much as you can about your guest’s positions, then take the opposing point of view.” It’s the classic “devil’s advocate” advice. I’d say, in general, watch out for being too enamored with your guest’s point of view on something. Asking a question that starts off with “What do you say to those who say… [insert the opposite view…] enhances your credibility. People listening who do have that opposing viewpoint get their chief question addressed. Listeners who agree with the guest are clear about how the guest defends against the criticisms.

The “Catch-All” ending. Reporters differ on this one but I’ve found it useful. Try ending with “Is there anything that I didn’t ask you about that you wanted to say?” Sometimes that will allow them to recap their main points in a succinct way, but it might also allow them the chance to get off their chest that bombshell that they really wanted to unload but that you, in fact, didn’t ask them about. Of course, sometimes it just means they give you another pass at a propaganda line that you weren’t that interested in to begin with, but there’s no harm in letting them feel like they got the last word in just they way they had hoped.

Paul Ingles’ vox-pop interviews on John Lennon:

Judith Krummeck (Host, WBJC-Baltimore)

- The most arresting interviews are the ones that sound like an intimate conversation upon which the listener just happens to be eavesdropping. Obviously, one’s most important function, as an interviewer, is to ask questions, but don’t be afraid to make open ended statements too, as one would in a conversation. Maybe they’ll disagree and that will make wonderful radio!

- Be prepared to use a fraction of your research material — but you can’t research enough.

An interview should sound spontaneous but it shouldn’t be off the cuff. The more you know the more the interviewee will sense that and be put at ease, and the more you know the more comfortable you will be to allow the interview to take its natural course. Read the press releases and comb the Internet to find out as much as you can about your subject, and try to do this ahead of time so you can think about it and let it simmer.

The best questions float to the surface when the material becomes part of your psyche in this way.

- An interview should have an arc. Think about a beginning, a middle and an end. Then be prepared to let that go out of the window if the interview develops a momentum of its own. This will not be alarming if you’ve done the research and absorbed the material. When planning the interview the first question is the most important but it’s not the most difficult; it’s to set the scene and to warm up your interviewee. Then you can explore the meaty stuff. Find a way to pull it all together at the end so that the interview doesn’t just wind down inconsequentially. Know exactly how you want to approach the interview — and then just let go and LISTEN.

- Never, ever tell the interviewee what they already know. (As in “You’ll be playing Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto” or “You studied at Juilliard” or “You conduct the such-and-such orchestra”.) There are many ways to get the information across to the listener without resorting to this technique. You can simply insert a phrase like, “I believe, I gather, I understand” to soften it. Or you can be inventive about how to incorporate the information into the question: “As you approach this performance of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto…”, “When you studied at Juilliard…”, “As the conductor of such-and-such orchestra…”. There are countless ways, and it makes it sound much more like the natural exchange of ideas it should be.

- Don’t lead the witness. Lawyers should never ask a question to which they don’t know the answer, but we in the media have the privilege of being surprised by our interviewees. We are just the facilitator. Give them the latitude to take the interview where they want to. You can present them with all the potential to give the best possible interview but ultimately it is up to them. Let go! Allow them to be true to themselves, good or bad. It’s ALL about them.

Judith Krummeck interviews musiciasn “Chad Bowles, practicing what he preaches”:

Michael Krall (Program Director, WBHM-Birmingham AL)

Interview Techniques

- The Overview. When interviewing musicians, always research their music or, in the case of classical musicians, the piece being performed, and try to find something unique about it. BUT, don’t ask about that specific bit right away. Better to start with a general question such as “Your thoughts on this work?” or “What’s the story behind this song?”

Why? It’s better for the listener to start with an overview before drilling down to specifics. Also, the guest’s answer may surprise you, lead you in a new direction you hadn’t anticipated, and can make for even more stimulating conversation.

- Mixing in Music.

In postproduction, make every effort to mix in an excerpt of music during the interview. It helps the audience better grasp the music (even if they think they know it), but it also draws listeners further into the interview.

- Ask For a Retake.

Don’t be afraid to ask the guest to repeat an answer. Perhaps the guest is not being as clear as you would like, or there was extraneous noise such as beard rubbing, a cell phone, or accidentally hitting mic. This is particularly important if you’re producing a montage or audio postcard where the guests’ answers have to stand alone. Politely remind them to repeat the question you ask. So, your question, “How long have you been playing guitar?” translates in answer form to “I’ve been playing guitar for 25 years.” As opposed to something completely out of context like “Twenty-five years”.

- Get to the Emotion and the Circumstances Behind the Music.

Music is powerful and can affect us on several levels. Tap into the emotion and stories and you’re bound to get good answers. Questions like:

- What do you feel when you’re performing?

- What do you hope someone will experience during your concert?

- What was life like for Shostakovich at the time he wrote the 5th Symphony?

- Keep Yourself Out of the Question.

While your having been to a concert or experiencing the music is helpful in preparing an interview, your audience doesn’t care that you saw Mr. World-Class Violinist five years ago, or when you heard the artist’s CD it made you think of pizza, Scrabble, Mozart, etc…

Michael Krall interviews “The B-52s”:

Boyce Lancaster (Host/Producer, WOSU-Columbus OH)

Interviews… and how to survive them

In my career, I’ve had some great interviews and some disastrous ones. Some of these suggestions seem simplistic and silly… until one of them happens to you.

Technical Tips

- Sure your recorder has batteries… but take a power cord anyway.

- Take extra batteries! (And make sure they’re fresh.)

- Test and be familiar with your equipment before you leave.

- Make sure you have blank recording media.

- Make sure you put it in the machine.

Interview Tips

- Make a list of bullet points rather than questions… things you want to be sure to cover.

- Be prepared to not ask any of your questions… not because it was a bad interview, but because it was a good one. Some of my best interviews have come when the conversation I was having with an artist or composer was so interesting that I never looked at my list.

- Know your interview subject well enough that you CAN have the conversation without looking at your questions. Getting locked in on the questions can cause you to miss wonderful opportunities for compelling conversation, which can turn into GREAT RADIO.

- Think like a listener… not like a music announcer. Sometimes informing and entertaining our listeners’ means asking simple questions in a simple way. Usually a shorter, more concise question leads to a better answer. Let Kafka do his own interviews.

- Set your curiosity free.

Boyce Lancaster interviews musician Hopkinson Smith:

David Schulman (Producer, NPR Musicians in Their Own Words)

Interviewing Feng Shui

Some thoughts on interviewing “feng shui”…

We know this: some people freeze-up in front of a mic. Some people turn into “public speakers.” Some people get really hammy. Some channel their inner maître d’.

Self-consciousness is the problem, and the challenge is to find a way — and there are so many ways to coax the person you’re talking with to a state of mind where they are centered on a “third place.” Not focused on themselves, not focused on you, but caught up in a third thing that they are so engaged with that they forget themselves.

I think this is what it means to make the microphone “disappear.” Graphically, what doesn’t work (for me, anyhow) could be represented as a straight line — two points facing only each other. It’s a static, oppositional shape.

For interviews where the point is to hold someone accountable or elicit reluctantly given information, it may be the ideal shape. For most of the interviews that I do, though, I want the interviewee to be comfortable. I want them to trust me, and confide, and laugh. I want them to share quite personal reflections, stories and memories. For this kind of interview, what I think works best is a conversational dynamic you might diagram as a triangle: two faces able to look at each other, but also able to turn and consider a third place.

Along these lines, I’ve become increasingly aware of the impact of certain mundane things that seem to have nothing to do with doing a good interview. But, sometimes, it seems like mundane things can change a dumb question into an evocative one. Here’s some of what I mean:

- What are the qualities of the physical space where the interview takes place?

- How do we sit or stand with respect to the person we’re interviewing?

- What’s the conversational impact of the way the recording gear is set up?

I want the triangle, not the line — so I try to set up for an interview space with angles and asymmetries in mind. Instead of sitting directly facing someone, I prefer to sit at an angle, and close — almost knee to-knee. I hold the mic close, but off to one side of the person’s mouth — so that there are no pops, and that the image of the mic is only in their peripheral vision as we look at each other eye-to-eye.

Sometimes you can get this triangle dynamic thanks to the engineer recording the session — the third person can sometimes encourage the interviewee getting to that “third place.” Sometimes you can get the triangle dynamic by handing someone a physical object (a book, a CD, a fruit, a business card with a term written on the back) that you ask them about.

For edited radio interviews that are much longer than clips taped in the field, we need to record in quiet spaces. But the quest for pristine sound can also make interview subjects uncomfortable. A studio can become a fishbowl, and fish generally don’t do so well in interviews.

What’s more, the design of many studios often enforces a rather formal distance of six feet or more between interviewer and interviewee, and then there’s all the obvious technology of our interrogation business. So, personally, I often prefer to record one-on-one in an apartment or hotel room (unplug the fridge and turn off the AC, of course… ).

Whether working in a studio or not, here are some questions about the physical space that I think are worth considering:

- From where the interviewee will sit, what will she see as we talk — something pleasant but unchanging? Something unchanging but unsettling (an unkempt tangle of wires)? Something possibly distracting (a window, a clock, an engineer at a computer screen)?

- What is the interviewee’s seat like? Try it yourself beforehand.

- What are the sightlines like? Does anything get in the way of making eye contact? When you do, what will be in the interviewee’s peripheral vision?

- How close should I sit? What distance will best encourage intimacy in conversation? If you are a smaller person, very close may be best. If you are 6′ 5”, conversational intimacy may be enhanced by sitting across a table from your interviewees and giving them more physical space. Experiment.

- Do I want to sit directly across a table from this person? Or at an angle, almost knee-to-knee? What positioning best fits the interview subject, the topic, and the way I anticipate the interview will go?

- How can I make the gear “disappear?” What is the conversational impact of the physical appearance of the mics I can choose? Do I use my pistol grip if it feels to a nervous interviewee that I am indeed holding a gun to his head?

- Do I tend to fumble with my gear in a way that breeds anxiety? Would having someone else engineer the session and serve as a foil add to the sense of “triangularity” and make the interviewee feel more comfortable?

- Can I orient my recorder so that I can see the meters and lights, but the person I’m interviewing can’t see them? Would it be less distracting if I had a cloth to drape over most of it?

- Does he seem to talk to me with a different attitude or formality when I put headphones on? What happens if during an interview that’s feeling stiff, I pull my headphones off for a moment, and try to get the conversation going again in a “normal” rhythm — interrupting, going outside the “topic” of the question at hand — without turning off the recorder?

When doing a remote interview — e.g. a tape sync — it’s still important to account for many of these things. So during initial set up, it’s worth asking an interviewee to describe quite specifically what exactly they see from where they are sitting. Wall colors, lighting, the recording equipment, other people. You could even use this as a cue for the on-site engineer to check levels. It primes the person you’re interviewing to be descriptive and specific. And in the process you may suss out unseen aspects of the recording set up that could distract or intimidate them.

David Schulman’s vox-pop interviews with musicians:

Julia Figueras (Host/Producer, WXXI-Rochester NY Backstage Pass)

Getting Beyond the Bio

If a guest is in for the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, I’ll ask how rehearsals went as a set-up question or if/when he/she last worked here (have you worked with Christopher Seaman before?). This can often lead to interesting philosophical insight on the balance of the artistic vision between soloist and conductor. The transformational questions (what changed your life, etc.) often show up toward the end of my interviews, since they are often the ones that result in the wonderful, squishy final answers that leave us slightly weak in the knees, feeling personally moved.

Multi-guest interviews are really tough, and require thoughtful stage management. Unless you’ve got a quartet in the room, anything more than three is hard for you to manage, and difficult for the audience to follow. Use names, and direct your questions specifically (“Chris, do you LIKE Chopin?” “Bob, does your chorus know you ran off with the take from your last concert?”). An interview is NOT a democracy, so everyone doesn’t get a shot at the same question. Someone may chime in with, “I’d like to answer that…” and that’s great. Getting the guests to respond to each other is marvelous. I actually had an argument break out among three musicians once. Frankly, I let them fight it out. It made for great radio.

Try to pick up on special talents within the group (founding member/newest member/arranger/treasurer) and zoom in. Not only can Sally explain what she does to keep the books of the orchestra balanced, but also John can talk about why she was chosen to do the job.

My biggest advice for all interviews is LISTEN! LISTEN! LISTEN!

Your guest has so much to share with your audience, and you probably don’t know all of it, despite your brilliant research. You are in the midst of a conversation, and your questions should be springboards for that conversation, not a rigid outline to be followed. If the guest compliments your outfit on air, say “thank-you” before moving on. You aren’t going to get to everything, so don’t even try. It’s your room, but you aren’t the star. That honor goes to your guest, and your job is to make their star shine.

Julia Figueras interviews musician Kathleen Bride:

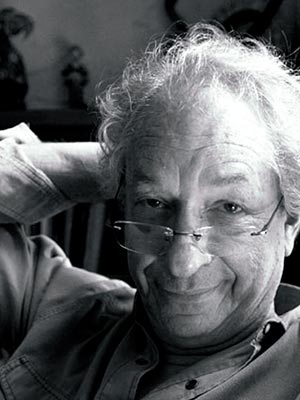

Martin Perlich (Author, The Art of the Interview )

)

Chapter Eleven: Re-Viewing the Interview, excerpted with permission from Martin Perlich and Silman-James Press:

Interview as Occupation

The job of interviewing is a Renaissance man or woman’s dream come true. You get to meet people from every conceivable walk of life, at all different points in their journeys and at different levels of success (or failure), and get paid for learning about them, relating to them, and then passing that information on to others. What other career allows you to explore the best (or at least the breadth) of human kind in such a way that brings value to you — in the form of both experience and money — to them, and to the infinite number of audience members who may come across what you’ve documented? Sometimes a seemingly small assignment will have huge implications; sometimes it’s practice for an upcoming challenge. But the job of interviewer can stay fresh for a lifetime.

Interview as Science

There is a science to interviewing that is at play no matter how intuitively one is able to arrive at it. The action/reaction of questioning and the answers it provokes, the chemistry of the emotions (both for the subject and the interviewer) and the accuracy needed to deliver the data — these aspects can all be mapped and charted. To treat your role with care — even meticulousness — can help facilitate the higher levels of the interview process.

Interview as Art

Finally, be assured: a great interview can “make art.” A pretentious formulation, perhaps, for a humble journalistic format currently spreading across all media like a fine mist. But since there is no agreement on the definition of what Art is, I humbly and provisionally propose the following elucidation:

- Art is the creation of something beautiful where it didn’t exist before — moving, insightful, socially valuable, exalting, transcendental — all of these. And, yes, a first-rate interview can meet any or all of these requirements, contain all these qualities, deliver all these essentials.

- Do what Art does. Look deep into your guests and connect their work with their souls. Yes, souls. Ultimately, communication is about sharing what is True with each other. You, as interviewer, are acting as a conduit between the heart of your Subject and the ear of your audience — those you serve. To practice listening for that Truth yourself, and then passing it on to others, is the purist element of Artistry.

- When a ‘sentient being’ (ordinary person) looks at a Buddha, he/she sees a sentient being. When a Buddha looks at a sentient being, h/she sees a Buddha.

- What I draw from this is that in seeing the Buddha (highest) part of a Guest, the Host activates the Buddha in him/herself, and therefore the audience.

Martin Perlich interviews Frank Zappa:

David Srebnik and Cynthia May of Virtuoso Voices collected the contributions to this guide. Check their their Virtuoso Voices Performer Clips series and Fundraising Messages at PRX. Thanks to the Knight Prototype Fund for supporting this Transom Online Workshop resource.