«Missouri River • Great Plains • Rocky Mountains» | «Radio • Writs • Ride • Resources»

Playing cards, Flathead Reservation 1905- Edward H. Boos |

There's something about Americans that compels us to commemorate the anniversaries of significant events in our history. We have, most recently, endured this nation's Bicentennial (1976), the Columbian Quincentenary (1992) and, at least in Montana, the Centennial celebration of statehood (1989). Perhaps because America is such a new nation, these milestones take on greater importance; at least I don't recall any MCC-centenary celebrations in 1953 to celebrate the founding of Rome, although I admit to having been pretty young at the time.

For Native Americans, the excitement surrounding these occasions have been somewhat puzzling. Certainly, American Indians found the notion of celebrating the "discovery" of this continent by Christopher Columbus offensive. The American Indian response was to stage protests aimed at drawing attention to 500 years of oppression, disease, alienation from the land. In 1976, those irritating "Bicentennial Minutes" passed by without any brown faces and only served to remind American Indians of how alienated we are in the land of our nativity. In Montana, communities celebrated the 100th anniversary of statehood by hosting cattle drives, the "Running of the Sheep," cowboy bands and the general chest-beating commemorating the spirit of those ancestors who braved the barriers to westward movement to settle this once wild and untamed land. Never mind that those "barriers" were Native peoples trying desperately to retain the passing ruminants of their fast changing culture. Never mind that these celebrations flaunted the loss of 93 million acres of tribal land.

For Native peoples, there was no single-minded response to these milestones. The Bicentennial and Montana's Centennial were largely ignored by its Indian citizens (although there was talk of an authentic Indian raid on the Great Montana Centennial Cattle Drive: if successful, a lot of needy reservation people could have been well-fed). Some Native Americans acknowledged the Quincentenary by participating in demonstrations in condemnation of Columbus. Indian people and their supporters attempted to disrupt parades in major cities across the nation, much to the dismay of the Italian-American community. Caravans of students traveled to San Francisco to meet and greet an ancestor of the Great Admiral as he attempted to sail into harbor in a replica of the Santa Maria. Other Indian people and organizations elected to use the Quincentenary to honor the survival of Native cultures or their contributions to world civilization. Thus, the pervious milestones were commemorated, condemned and ignored, but certainly never "celebrated."

Custer's scouts (Crow), Little Bighorn 1890? |

So, the idea of celebrating the up-coming anniversary of the "Corps of Discovery" isn't such a cut and dried deal. Problem One is that "discovery" word. Native people didn't like it in association with Columbus and we haven't warmed up to the notion a whole lot since. Still, this phrase doesn't seem to draw same kind of negative fire that was noted in 1992. Maybe some Indian folks think it's the "Corpse"of Discovery and imagine that America has adopted the Hispanic "Day of the Dead" holiday.

Problem Two is that Native people don't see the Expedition as anything about which to get excited. One can get aroused about Columbus, who, justly or not, is often blamed for the enslavement of indigenous people and millions of deaths from disease. The Expedition seem less directly to blame for such historical degeneration. After all, Lewis brought his own slave and Clark may have contracted syphilis (ironically, the source of which, among the Natives, may have been Europeans) from one of his Native hosts (some scholars content that Clark's suicide was a result of the degenerative character of this disease).

Whatever the case, for Indian people, celebrating the visit of Lewis and Clark doesn't make much sense if there isn't even a tribal memory of it. (A digression: Peter Ronan, in his History of the Flathead Indians, tells one recollection by an elderly woman named Ochanee. According to this account, Captain Clark took a Flathead woman as his temporary companion and she had a son as a result. This son, named Peter Clark, lived to old age. This story is one not found in Stephen Ambrose's book, Undaunted Courage, THE bible of Lewis and Clark fans.)

So, what should the response from Native America be toward the Corps of Discovery?

Sioux scaffold grave, near Jordan MT 1996- L. A. Huffman |

In January 2002, I was in southeastern Montana, specifically at Poplar, the capital of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation, to do a presentation entitled "Lewis and Clark Among the Indians of Montana." The audience consisted of faculty, administration and students at Fort Peck Community College and a few local Lewis and Clark buffs. Most of the audience were Indians; either Assiniboine or Sioux.

My presentation was pretty typical of Lewis and Clark programs, a kind of "Bill and Meriwether's Excellent Adventure." After all, there is nothing new under the Lewis and Clark sun. One of my major points is that most people assume the Expedition's contact with Indians was 50 separate meetings with the same people. On the contrary, each encounter with an Indian tribe was unique as each possessed its own culture and history. Naturally, this point did not go unappreciated by this audience of Assiniboine and Sioux.

My other important point is that the Expedition forever changed the landscape of Montana. The Milk River marks the western boundary of the Fort Peck Reservation and is some 50 miles away from Poplar. The Expedition named the river, the Milk, "from the peculiar whiteness of its water, which precisely resembles tea with a considerable mixture of milk." This river was known to the Hidatsa as "The River that Scolds the Other," because as this river flows into the Missouri, it travels side by side with the Missouri for a short distance before giving up its identity. And what does your official Montana highway map call this river today? That's the impact of the Coups of Discovery. Montana carries little of its Native character as measured by current place-names.

Mine wasn't the only Lewis and Clark show in the neighborhood. A week earlier, Gerald Baker (Mandan-Hidatsa), superintendent of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and Otis Half Moon, Nez Perce elder and cultural expert, were in town to speak to the tribal council of the Assiniboine and Sioux tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation. They were there to warm up Indian folk to the up-coming jamboree.

As it turns out, my message was much the same as Baker's; "they're coming and there's nothing you can do about it, so you might as well cash in as best you can." No, not Lewis and Clark, but tourists, following THE Trail. They're bringing their cameras, copies of Undaunted Courage and their American Express© cards. And the Fort Peck Reservation is, for the most part, totally clueless about what to do about that.

That's not the case in other communities along the Trail. There is an entrepreneurial spirit sweeping Montana. One can follow bits and pieces of the Trail on horseback, foot, bicycle, hot air balloon, snow machine and water craft, under the watchful eye of naturalists, historians and storytellers, all commercial enterprises of one sort or another. The Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Interpretive Center's Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Training Academy at Great Falls sponsors workshops on how to get into the act. Workshop sessions are "Lewis and Clark's Journey Through Montana," "Lewis and Clark as Montana Naturalists," "Montana Indian History and Culture," "Public Speaking, Storytelling, Interpretive Techniques," and "Visitor Service and Tour Services." One can take 5 workshops (at $120), after which you, too, can become an officially recognized "Lewis and Clark Guide." What is really needed is a session entitled "How the Hell Do You Get Them Tourists to Stop?"

It's all about location, location, location. To the east of the Fort Peck Reservation is Washburn, North Dakota, near where the Party spent the winter of 1804-05. Washburn has "Lewis and Clark Days," complete with a parade, buffalo barbeque, reenactments, lectures and demonstrations. To the west of Fort Peck is Great Falls, with the aforementioned Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Interpretive Center (don't forget the "Lewis and Clark Festival," complete with a parade, buffalo barbeque, reenactments, lectures and demonstrations!). There you can observe a cultural exhibit, developed with contributions of the Crow, Blackfeet, Nez Perce, Salish, Pend'Oreille, Hidatsa and Shoshoni.

What is frustrating for the Assiniboine is that there are no Encounters to tout. The Expedition met no Assiniboine. Lewis and Clark took two days, May 7th and May 8th, 1805 to cross what is now the Fort Peck Reservation. No one is certain where their campsites were and save the River that Scolds the Other, little other reference exists that they were there. So, therein lies the problem: how do you get these thousands of tourists to pull off at Brockton, Poplar, Wolf Point, Oswego or Frazer? If you can get them to stop, what do you have to show them?

The Them is important. You can basically forget those who come by bicycle, or on foot or up (or down) the river by boat (or jet skis or kayaks). These folks, with the exception of Josef and Barrett, are cheap bastards who got something else on their agenda. They're not going to spend any money as evidenced by all the Top Raman® noodle wrappers in the recycling bins. The real visitors, the contemporary Corps, are driving R.V.s, 5th wheels, motor homes, campers and vans. These are retirees with money and who are well-read, already somewhat familiar with the Expedition. And, they are selective. They want a "meaningful experience;" a chance to "touch a historical moment." No "Largest Ball of Twine"© for them!

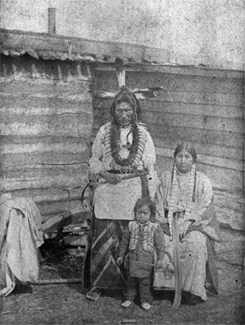

Fighting Bear & family Last lodge of the Mandan Fort Berthold, Dakota Territory 1880- G. L Curtis |

There are other communities like Poplar, not stellar stops on the "Discovery Paths" and without a museum, festival, parade, buffalo barbeque, reenactments, lectures or demonstrations. Not that Poplar doesn't have plans. Fort Peck Community College will host an Elder hostel-type program, more academic than sightseer focused. Designs are for sessions on ethno-botany, for example. Good stuff. But how, short of Road Spikes® across Highway 2, do you get the "average" tourist to stop? Why should they, when it's only 340 miles to THE Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Interpretative Center, complete with certified "Lewis and Clark Guides?"

One administrator at Fort Peck Community Colleges suggested, in jest, that the community round up all the 2 - 8 year old, doe-eyed little boys and girls, dress them in "authentic" Indian garb for a "your-picture-taken-with-a-real-live-Indian" booth along the highway. In a way, that would be the easiest path to take. A reproduction of village life along the Missouri. An interpretative center of some sort. Maybe include an exhibit of local flora or fauna. Highlight the grizzly bear, wolf, elk and beaver; animals noted in the Journals, animals not seen in these parts for generations, animals years ago driven from Missouri River valley to the high mountains to the west.

This is what the tourist may want, but is this the story the community wants to tell? Or should tell? Should the roadside attraction be a tour of the Poplar Community Hospital Diabetes Clinic or the Spotted Bull Treatment Center? Should the story include the historic inequities that has contributed to the high alcohol consumption or acts of violence against family so endemic here and on other reservations? Should the story be the triumphs over alcohol and cultural rediscovery? The beauty of the star quilts given away at basketball tournament? Should this opportunity be used to enlighten or entertain? Enlightenment is painful; entertainment empty.

Yes, they are coming. You are coming. What do you expect? What do you want?

# # #

Shoshone war dance, Fort Washakie WY 1884

Dr. Walter C. Fleming is an associate professor in the Native American Studies department at Montana State University, Bozeman. His doctoral degree is in American Studies from the University of Kansas. He has taught American Indian history and culture courses at the university for 23 years and is a specialist in Northern Plains Indian culture and American Indian Literature. Fleming is also associate curator of the Native American collection at the Museum of the Rockies, Bozeman.

Professor Fleming is co-author of Visions of an Enduring People and numerous book chapters and articles. He has written on federal Indian policy, affirmative action, contemporary issues, American Indian literature and the impact of the Lewis and Clark Expedition on Montana tribes.

Fleming is an enrolled member of the Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas. He was born on the Crow Indian Reservation (Montana) and raised on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation, also in Montana. He is a traditional native dancer and a member of the Gourd Dance Society, a traditional society of the Southern Plains.

Issue of rations, Blackfeet Agency 1926

«Missouri River • Great Plains • Rocky Mountains» | «Radio • Writs • Ride • Resources»

©2001 Barrett Golding / Josef Verbanac

![]() Funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting

Funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting