My Father’s Music

6:48

Rebecca Flowers

6:48

Rebecca Flowers

A daughter and dadís syncopated relationship.

Broadcast: Jun 18 2007 on HV PODCAST; Jun 18 2004 on NPR All Things Considered Subjects: Family, Music, Jazz

Commentary: Remembering growing up with a cool father

June 18, 2004 from All Things Considered

MELISSA BLOCK, host: This is ALL THINGS CONSIDERED from NPR News. I'm Melissa Block.

MICHELE NORRIS, host: And I'm Michele Norris.

Sunday is Father's Day. For commentator Rebecca Flowers, the weekend conjures up a mix of memories both paternal and musical.

REBECCA FLOWERS:

In 1976, my family lived in a split-level ranch house on an acre of country land in a brand-new subdevelopment. My brother was 12. My mother was a librarian. And my dad--well, he was quite possibly the grooviest guy in the small town of Wadsworth, Ohio.

(Soundbite of music)

FLOWERS: Joe Cool, my mother called him. He wore muttonchops, love beads and a leather vest.

(Soundbite of music)

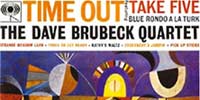

FLOWERS: He listened to Bread and Chicago and old jazz, guys with names like Miles and Bird and Dexter and Thelonious. And he spent all his time at home playing keyboard.

(Soundbite of music)

FLOWERS: We had the only basement rec room with a baby grand piano and an electric organ. And my parents were known to frequently burst into songs like `Five foot nine, eyes that shine, face that looks like Frankenstein' and "Cocaine Bill and Morphine Sue." They would do this in front of anybody who happened to be eating with us, including our friends. I was 11 years old, and it was stuff like this that made me want to run away from home.

(Soundbite of music)

FLOWERS: So Christmas of 1976, there's a special present under the tree. My brother and I rub our eyes, unsure of what we're seeing: smoky gray drums with silver flames licking up the sides. It is, in fact, a drum kit. My brother races over to inspect it while I desperately look around the room for my real gifts. Then I hear my father say, `No, the drum kit is for her.' My first thought is, `But that's not a pony or an Easy Bake Oven.' My second thought is, `Oh, my dad thinks I'm going to play the drums.' Now my father is a natural born musician. I've seen him pick up and play a recorder, clarinet, a trumpet, harmonica, a baritone saxophone, a banjo, a 12-string guitar, almost anything. That wasn't me. I'd already failed at both piano and clarinet. But my dad refused to believe that I didn't have some shred of his musical abilities. And so, drums.

After dinner every night, we'd head down to the basement rec room together to have a little jam session before my bedtime. It became our special way of spending time together. It was great to have his attention, but deep inside, I was afraid of discovery. I lived in fear that one of my friends would stop by and find my sitting there in my Holly Hobbie pajamas, keepin' time to "Green Onions." But I soon came to realize that my drumming career was meant to serve a higher purpose. It was really so I could keep time for him while he practiced. And maybe somehow having this white suburban kid in ponytails and braces flailing away on a set of secondhand Yamahas made him feel just a little bit more like a real jazz man.

I only became more self-conscious as a teen-ager. I wanted to be popular and have dates. And I was horrified to discover that none of the popular kids stayed inside on the weekends to play jazz with their dads. So I began to resist. After dinner, instead of automatically following him downstairs, I'd flop on the couch in front of the TV or bury myself in my homework. He retaliated. He played the numbers he knew were my favorites, hoping to tempt me to come on down and hitch up to the old skins. When this didn't work, he would sometimes resort to his secret weapon. He'd play the opening bars of "Take Five" over and over and over. It's only four or five notes and hooks easily back onto itself.

(Soundbite of "Take Five")

FLOWERS: And as we were all to discover, it's maddening when repeated over and over. You're just dying for the saxophone to come in there and get the damn thing moving. I would ignore him, turn back to the TV, but we could still hear him, stuck in his melancholy moment with his accompanist. I wanted to scream, `I am not your human metronome, man!' I thought I might have preferred one of those dads who watched basketball games and drank Miller beer, who mowed their lawns on the weekends and didn't insist on making their kids learn 5/4 time or paradiddles.

I don't know how this battle ended. I guess he just gave up on me. I moved on to other things, the things kids do in a small town like Wadsworth, Ohio: drinking and driving, playing cards after school and smoking. Then for some of us, Big Ten college. After Big Ten college, there was Big Ten graduate school. That meant a lot less football and a lot more good books. And suddenly I found that you couldn't listen to Madonna and Prince while reading Freud and Sartre. I asked my dad to make me some tapes, and he did, and I would sit in my '50s-style furnished apartment and read my good books and listen to Thelonious Monk and wonder that I hadn't really heard it before.

(Soundbite of music)

FLOWERS: From then on, all the guys I really liked seemed to have one thing in common: They loved jazz, just like my dad, Joe Cool. Skiing in his trench coat at Vail because he forgot to bring his ski jacket, soaking in a hot tub wearing a fur hat with ear flaps, shoveling the driveway in his bathrobe and cowboy boots. If ever there was a guy who did his own thing, who was really cool, it's my dad.

I will probably never be that cool. But who knows? Maybe one day when my daughter is a teen-ager, her friends will drop her off after school, and there I'll be in the front yard, raking up leaves in an old bathrobe and a pair of boots, swatting the air with my make-believe sticks. `Hey, honey. Hi, sweetie.' And my smiling daughter will turn to her friends and say, `Isn't my mom the coolest? Hey, where you going?' Or she'll run shrieking into her bedroom and never come out again.

(Soundbite of "Take Five")

FLOWERS: (Singing scat along to music)

NORRIS: Rebecca Flowers lives in western Massachusetts. She's expecting her second child on Father's Day.

(Soundbite of "Take Five")

(Credits)

BLOCK: I'm Melissa Block.

NORRIS: And I'm Michele Norris. You're listening to ALL THINGS CONSIDERED from NPR News.