From Afghanistan

Mazar →Sherbigan →Qala-i-Jhangi →Kabul

Getting Oriented, Mazari-I-Sharif

Just in town, I decide to go for a walk. I leave the hotel, cross the street to the mosque, and gaze up at the blue tiled dome. The instant I stop walking four or five young men also stop walking, as if they’d just been pretending to be going somewhere. They stand right in front me. Then quickly there are ten, then thirty, fifty — all boys and men, crowding close together, a hundred eyes looking at me in disbelief.

“America,” I say, wondering if this is wise, because we’d just bombed their city and their country. But it’s the word they want to hear, they want to say it. America… America… America…

“California.” I say, wanting to hear it echo. “Mississippi.”

Three or four try to speak English. “Hello, how are you?” “Thank you very much.” “Okay, good luck, good-bye.”

“What do you think about America bombing your country?” I ask the first boy. “Was it a good thing or a bad thing?”

“It was a good thing. When the Taliban here there was no working, nothing working. Now America comes here. Is it correct? America comes here?”

“You mean will American soldiers come here? I don’t know, maybe.” He translates this for the crowd and they start shouting questions, too many to translate. Sort of frustrated, he says, “We want money to make work. We want now the schools.”

“I think there might be some money, but I don’t know, we might start bombing some other country and forget about Afghanistan.”

This makes the yelling get louder. They’re not yelling at me, just yelling for the sake of yelling, filling the space with their voices. I look down at a guy in a small cart. One of his legs is missing and the other is very short, like a baby’s. He says he needs a new cart, a real wheelchair with bicycle tires like they make in America, and some artificial limbs like they make in America, and he wants to know if I can get him some.

“I don’t know how to do that,” I say, “but it’s possible. I think that’s one of the things there will be money for.” They just keep pressing in, getting closer and closer, and it’s time to get going. So I say, “Okay. Good luck. Good-bye,” and wave and quickly back into the hotel.

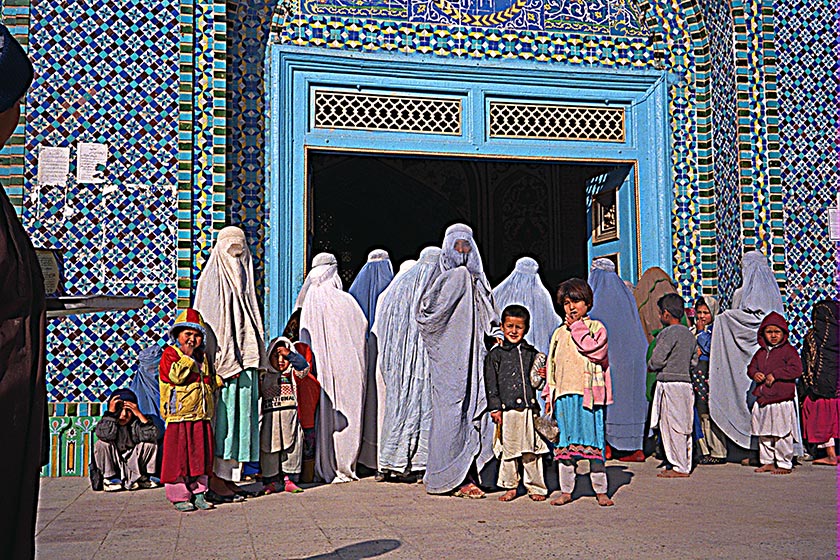

Mazar-i-Sharif, which means “tomb of the saint,” is a city of adobe tenements that look ancient, all somewhere in the process of crumbling and collapsing. In the street men pull carts with wooden wheels, others are pulled by horses and donkeys, carrying wood and bricks. There are shops with skinned goats hanging upside down out front, shops where chairs and tables are made, shops with material for clothing and drapes. Subtract the cars and the shop where the guy is making satellite dishes from pieces of scrap metal, and ignored the occasional Russian-made proletarian concrete building, then the city would look 13th century, or even older.

Again I go out for a walk, and again I stop, and again four or five men around me immediately also stop, and again a crowd quickly forms. This time I pull out my camera and start taking pictures. They become quiet and still — not afraid or shy of the camera, but also not quite sure of its power. I hold it at arm’s length down low and they stare straight at the lens and I take their pictures. While I’m doing this I hear a voice, a soft, calm voice next to my ear say, “Excuse me, are you a journalist?” I turn and see a young man with a shaved head — kind of startling — and say, “Sort of.” He’s wearing a Planet Hollywood tee-shirt over a brown turtleneck, checked polyester pants two or three sizes too big and cinched by a belt — kind of a punk look, opposite of the others. And I have this feeling that he might actually be a woman. He has beautiful eyes with long lashes, and that soft voice. I look, twice, to see if he has breasts.

“What are you doing?” he asks.

“Just taking pictures,” I say. “How old are you?”

“Nineteen. Do you need a translator? I have been studying English in school, but there is no school now — the Taliban sent our teachers back to Turkey. I would very much like to work for you. I will help you in any way that I can, and I will not leave your side — as long as you are here I will be with you.”

“What’s your name?”

“Najibullah Niazi.”

“Najibullah. Why did you shave your head?”

“When the Taliban leave two weeks ago many men shave their beard, but I do not have beard, so I shave my hair,” he says, smiling.

“Good one,” I say, “but I’m sorry, I don’t have very much money and I just can’t afford to pay a translator every day.”

“For me money is not important. If you have money you can pay me. If you don’t have money you don’t pay me. When you are finished you can decide.”

I know that this is a deal that could go sour very quickly, but I do need a translator and, to a certain degree, I believe him. He’s trying to learn to look and act like a westerner, and probably the best way for him to do it would be to hang out with me. I wonder if his shaved head might frighten the locals, but then he is a local and it’s his business so I let it go.

“Come,” he says, “let’s go to the hotel and we can talk there.” We’ve attracted a large crowd, some of them spilling into the street, making traffic go around them. “This place is not so good for you.”

We walk through the crowd and they go on about their ways, all except for three very dirty little boys who try to stand in front of me and brush my hand begging for money, but all I have are 20-dollar bills. Naji saves me by scolding them away.

Mazar photo gallery

Mazar →Sherbigan →Qala-i-Jhangi →Kabul

On The Road To Sherbigan

Yesterday Najibullah told me that “The Titanic” was such a hit in Mazar that now if you want to say that someone is “with the latest style” you say that he is titanic. I’d say Najibullah is titanic. He gets there. I loaned him my sunglasses and hat and he thinks he looks like a U.S. Special Forces soldier, or actually he says that other people think he looks like this, that they can’t tell he’s an Afghan, and this makes him very happy. He’s driving the car — the old chauffeur is relaxing in the passenger seat, willing to let the 19-year old go ninety miles an hour across the desert — pounding the steering wheel to the beat of some Afghan disco music.

He drives too fast, and he slows down and speeds up too quickly. When passing big trucks on the left, the old chauffeur helps him out by saying whether it’s clear — the steering wheel is on the right side, as the car is from Pakistan. And always, when passing, he blows his horn for the entire distance. Everybody does. He swerves around the small potholes but crashes into the big ones. This happens again and again, even though I keep telling him to slow down.

Soon we come to the 3,000-year-old town of Balkh, sometimes called “the Mother of All Cities,” anciently called Bactria, perhaps the home of the double-humped Bactrian camel. Zoroaster is aid to have preached and died here. And then for a while it was Buddhist. The region was conquered by Alexander the Great in 329 B.C. It was taken by the Arabs in the 8th century A.D. They built one of the largest libraries in the world here, but it, and the entire city, was destroyed by Gengis Kahn in 1220. The mystic poet Rumi was born near and his family fled to escape the mongol hoard.

“Yes, it’s real. It’s the only one in Afghanistan, built by the Russians. The gas comes from the ground near Sherbigan and goes to Mazar, 160 kilometers.”

“And it actually works?”

“Yes, for electricity in Mazar. We have one five-megawatt station. My father, he helped in building this, as geology engineer.”

Up ahead a teenage boy with a Kalashnikov waves us over. It’s not a checkpoint, he just wants a ride, and we have to stop because he has a gun. It’s a common form of transportation for the soldiers. But when he comes up to the car the old chauffeur starts yelling at him, “What are you doing? You shouldn’t be out here stopping cars on the highway. This man is an American and you should be careful not to upset him or the bombs will find you in your house!” The kid falls back like he’s been punched hard. He looks truly frightened.

“He really believed that,” I say.

“Yes, they all believe it,” Naji says. “And it’s true.”

“Yeah, but I can’t make it happen.”

“But he does not know this.”

The old man looks at me and smiles.

Xanadu Redux

Dostum’s compound in Sherbigan resembles a Soviet Club Med in decline. There are two pools, one indoors and one outdoors, both empty and breaking apart. The outdoor pool is deep and has a diving platform, surrounded by a concrete patio with lights for night-time parties. The indoor pool is housed in the strangest building I’ve ever seen, made from concrete but fantastical in style, a mixture of Bauhaus and Dr. Seuss. The doors are chained shut, but I can see the pool through the broken windows — long and shallow, perhaps for the women.

In the center of the compound, which is about the size of a city block and surrounded by a wall, is Dostum’s residence, a modest two-story beach house. Beyond is a garden with long rows of rose bushes and fruit trees, sidewalks and benches, a small Mosque in one corner, and a large fountain, also made of concrete, in the shape of an opium poppy. A giant concrete poppy fountain, dry and out of order.

Only two weeks before this city and even this guest house had been occupied by the Taliban. (They cut out the heads of the deer in the pastoral murals in the hallways.) For three years these mullahs and commanders have been in hiding in the mountains, while Dostum was in self-imposed exile in Turkey and other places. But now he’s back. He’s dressed in velour like a medieval monarch — a big man with a round face, black woolly caterpillar eyebrows, and salt and pepper hair and beard trimmed short and neat. He looks like a big teddy bear, and I have a strong urge to give him a squeeze, but I don’t because I know he’s a powerful warlord who is reportedly so evil that his laugh has frightened men to death, and so cruel that he once tied a man to the treads of a tank and then watched as he was crushed into mincemeat. He sided with the Soviets during the 1980s and built his army by running drugs, although no one speaks of this. (And, by the way, no one writes of the essential relationship between guns and drugs in Afghanistan for just this reason — it’s too dangerous.) During the 1990s, when Afghanistan was torn by civil war, Dostum sided with everyone and no one, making and breaking many promises, and surviving when many others did not.

One of the older men, a mullah, stands and tells Dostum that his office in a near-by town has no furniture or carpets left, that the Taliban took everything. “Here you have new things,” he says, “but we have nothing left, not even a desk.”

Dostum takes this in stride and tells the man that these things will not be a problem, but that they will take some time. He has only just now arrived in town. A younger man stands, a commander, and tells Dostum that there are still Taliban soldiers hiding in bunkers outside his village and that they have threatened to die fighting before they surrender. Dostum tells him to tell the Taliban that their resistance is futile — either they surrender or they will be bombed by U.S. planes until there will be none of them left.

A man walks to the center of the room holding a sheet of paper in his shaking hands. He stands there and looks at the paper and then he starts to sing. It’s a dirge, with many verses, telling of battles where brothers and friends fought bravely but were lost. The men in the room are transported in space and time, some of them sob, tears falling onto the blankets around their chests. There’s something very heavy in the room. I can’t see it but I can feel it. These men don’t want to fight anymore. Not because they are afraid of fighting, but because they are really very tired of fighting.

The Hotel

The power is off in the hotel as well as the entire city of Mazar, but I have a head lamp and a box of wooden matches. The head lamp I brought with me, but the match box is from Latvia, and I can’t remember how it came to me. Maybe by way of the Moscow-based Boston Globe reporter on the fifth floor. They are fine wooden matches, “Avion,” with a picture of an old airplane. The box is also made of wood, and sturdy. It seems very exotic and very much out of place.

There is no power in this hotel and there is no running water in this hotel, and I’ve been waiting for an hour for a simple dinner to be brought to my room — a 4×8 foot space with a bed and nothing else. The bed is a steel-mesh hammock with a thin cotton mattress, two dirty sheets, and one blanket. There are better rooms in the hotel, large rooms with windows and kerosene heaters, but I’m trying to save money and this one costs only ten dollars a night while the others go for $35. I don’t mind the darkness, and I don’t mind the bed, but without running water the communal toilets are filling up and the stink is hard to ignore. No self-respecting foreign correspondent would stand for this, but there are no other hotels in town.

I’m hungry. There is a restaurant in town, but even those who’ve been there don’t know where it is. The sound man with the French TV crew said, “You take a taxi and say you want to go to the restaurant. It’s around here somewhere, and it’s a real restaurant, with tables and table cloths and enough light so you can see what you are eating. Not bad.” But it’s night now, and nobody goes out at night. Nobody. The hotel doors are locked and the dogs control the streets.

An hour ago I asked the ten-year old boy who works here if there was a way I could order something to eat. He speaks English pretty well, sometimes with an attitude if he doesn’t like you, but we get along fine because I tip him 10,000 Afghanis whenever he does something for me.

“Yes,” he snaps, “what do you want?”

“Do you have dinner?”

“Dinner?” like he’d never heard the word.

“Yes, dinner, like kabob. Do you have kabob?

“Kabob, no.”

“Rice?”

“Yes, rice.”

“And bread?”

“Rice and bread.”

“And tea.”

“Okay.”

“Do you have anything else?”

“What?”

“Is there anything else they can make in the kitchen besides rice and bread and tea?”

“No.”

“Okay then. Can you bring it to my room?”

“Yes, yes,” and he went off into the darkness and he has not come back. But there are many hungry people in this town, and I roll another cigarette and light it with my exotic matches and listen to the last prayer of the day being sung over a loudspeaker at the mosque.

Love Means You Never Have To Say You’re Sorry

I am standing outside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs waiting for the young Najibullah to tell the authorities of our plans. He must report in, he says, or they will get rough with him. So I wait. Next to me is a Toyota Tacoma four-door, four-wheel-drive, diesel pickup. Chrome roll bars, chrome bars over the front grill, chrome running boards. In the back bed are three soldiers. The one in the middle is straddling a floor-mounted machine gun with a bore the size of three fingers. The man to his left cradles a medium-sized machine gun with fold-down tripod so that it can be set on the ground or maybe a rock. The other soldier has a Kalashnikov over his shoulder. They’re waiting for their commander who has gone inside the building. The sun is out but it’s a cold morning, and two of the soldiers are wearing polar gear dropped from American planes as part of the humanitarian aid program — thick insulated pants, big coats with big hoods, and black leather lace-up combat boots. It would be really cold riding in the back of a pickup and these clothes are perfect for the job, so they’re styling. It’s cool to sit in the back of a pickup with a machine gun. It’s cool to be part of the conquering army on a bright and sunny morning.

I ask the men if I can look inside the cab and they say go ahead, getting out and coming around to watch me. The floors and the seats are covered with Afghan carpets that look like they’ve just been vacuumed. There’s no mud or dirt anywhere, which seems impossible considering that it’s been raining for days and there’s mud everywhere. On the dash there are red plastic roses, and the front window has little multi-colored cotton balls hanging from its border, and there are little stickers around the cassette player of valentine hearts and the word LOVE written in that 60’s psychedelic font. I point to the stickers and look at the soldiers and one of them says, “Taliban.”

“Taliban?”

“Yes,” he says and makes a motion with his hand meaning that the whole truck had belonged to the Taliban.

“Kunduz?” I asked, meaning ‘Was this truck taken at the surrender of Kunduz?’

“Yes, Kunduz,” all nodding their heads.

It’s strange that Taliban soldiers had decorated the cab this way, like a gay bordello, and it’s stranger still that the Northern Alliance soldiers hadn’t changed it.

What does this mean?

It means the Taliban were more cool, more hip, than the Northern Alliance.

The Hotel

I’ve been cold at night so before going to bed I ask for an extra blanket. I find the young man who sweeps the floors and say, “Blanket?” making the motions like I’m sleeping and pulling a blanket over my head.

“Blanket?” he asks.

“Yeah, blanket,” acting like I’m in bed and shivering.

“Okay, blanket,” he says and goes directly to a room just across the hall from mine and pounds on the door. The young man who answers also works in the hotel, also sweeping the floors. My guy tells him that I need his blanket, so hand it over, since I’m a paying guest and all. But the other guy says no way, Jose, it’s cold out tonight. My guy says, listen, you’ve got to give him your blanket, if you get cold you can go sleep with your friend downstairs. This makes the other guy mad and he grabs my guy at the shoulders and they start wrestling, pushing each other in and out of the room, yelling, knocking stuff over while I’m saying, “I don’t want his blanket, stop, listen, there must be another blanket in this hotel somewhere.” They stop wrestling and just yell at each other for a few minutes, and then they’re not yelling at all but talking quietly, and then they’re hugging each other in the doorway and holding hands.

“Blanket?” I say, rather perturbed.

No, they both shake their heads, no.

Balkh/Sherbigan photo gallery

Mazar →Sherbigan →Qala-i-Jhangi →Kabul

Fortress Of War

The mud in the basement at Qala-i-Jhangi is a thick brown mousse, eight inches deep. It makes a sucking noise when I step in it, and then sticks like clay to my boots. It smells of rotting corpses, because that’s what’s down here, some have been dead for seven days. There are two by the stairs, halfway cemented in the mud, faces swollen, the color of ashes. I walk carefully around them. There are more, a lot more, around the corner, but it’s dark in there and I don’t have a light and the smell alone is evidence enough.

I back out and go upstairs, neatly avoiding the unexploded mortar shells sunk into the wall. I stand outside the building trying to pick the mud off my boots with sticks from the shattered pine trees, ripped apart by U.S. missiles. When sticks no longer work I try scrubbing it off with snowballs packed from the three inches that had fallen and is still falling, blanketing the battlefield and the rubble, as in photos of the Battle of the Bulge or Wounded Knee. Workers, including a woman who isn’t wearing a burka, are going down in the basement and bringing up coats and shawls, dripping wet. They reek. I reek. I sit on what had been the front porch using a brick to scrape the mud off, and just to my right there’s a human foot, smudged and bloody, with a little patch of snow on the heel, snapped clean just above the ankle. Perhaps the body was obliterated with the front door, because there’s nothing there but a huge gaping hole.

They’d been in Kunduz, where all the Afghan Taliban surrendered by simply driving out of town and switching sides, suffering only hugs and kisses and the loss of their pick-up trucks. But for the foreign Taliban the decision was more complicated. The Northern Allilance Tajik commander had threatened to kill them all rather than take them prisoner, and Dostum had a history of massacres. Still, realistically, there were at least 4,000 of them and it would have been very difficult to slaughter 4,000 men on CNN. Also most of them were Pakistani Pashtuns, so it would have been politically difficult to kill them.

Dostum’s men took a long time disarming the Taliban, and then they very slowly began to search their bodies. But by the end of the day only some had been carefully searched. It was Ramadan, and Dostum’s men were hungry and not keen on getting blown up. This is when Dostum said, “Take them to my castle.”

Qala-i-Jhangi was fifteen miles away and had the advantage of being enclosed by a mud wall sixty feet tall, more than 400 yards on a side, with an elaborate stitch of crenellations, very medieval and huge, surrounded by a moat. Inside was mostly farm fields divided into three compounds separated by more high mud walls. The prisoners were taken to the third compound, a pasture with forty tethered cavalry horses. Also in this compound was a brick building previously used as a military classroom, and underneath this building was an air raid shelter, a basement, with thick concrete walls, built by the Russians.

The plan was to tie the prisoners’ arms and then put them in the basement, but before they could do this one of the prisoners blew himself up along with two high-ranking Northern Alliance commanders. Everybody hit the ground, and, to their credit, the other Northern Alliance guards did not start shooting. They pulled out and left the prisoners there for the night. During the night eight more foreign Taliban killed themselves in an explosion. But the next morning, even though the prisoners had been blowing themselves up, two CIA men (“Dave” and “Mike”), and two Red Cross directors from Australia and Swizterland went into the third compound. The Red Cross was there to ensure the humane treatment of the prisoners, but the CIA was there to interrogate them. It’s not clear what happened — either a prisoner rushed and grabbed Mike in a bear hug and blew both of them up, or a prisoner threw a grenade that killed a bunch of guards, or a soldier threw a rock at a guard, knocking him down and taking his gun and killing him and five others — but something happened and very quickly Mike was dead and Dave was shooting his pistol and a bunch of prisoners were shooting machine guns and the remaining guards fled the compound shutting the gate behind them, leaving Dave and the two Red Cross directors inside.

The three white guys and their associates found a way over the outer wall of the fortress while the Taliban found a huge cache of weapons near the stables. Why the prisoners had been put in an area with an arsenal of weapons was not clear. Some believed that the whole thing was a set up by the Northern Alliance. Others, including the commanding officer of the Northern Alliance, later said that they believed the prisoners could be contained in the basement and that they didn’t expect an uprising. But it happened. For the next two days there was intense fighting, the Taliban hiding behind trees and walls of the buildings, and climbing trees to shoot over the walls of the compound, firing rockets and mortars over the walls, screaming God is great and running into open fire and dying. Or just getting obliterated by a series of U.S. air strikes — precision missiles dropped from fighter bombers and artillery barrages from AC-130 gunships.

Because there were only 188 bodies in the pasture it meant that there must have been close to 200 other bodies down in the basement. Nobody went down there on Wednesday, but on Thursday some old men were told to start pulling out the bodies, which they did, only to meet with a spraying of bullets. One died and one was wounded; incredibly, there were men down there willing to keep fighting. They’d come out at night and cut pieces of flesh off the horses. They’d drank water mixed with blood from the floor of the basement. They’d survived the aerial bombardments, and still they would not surrender.

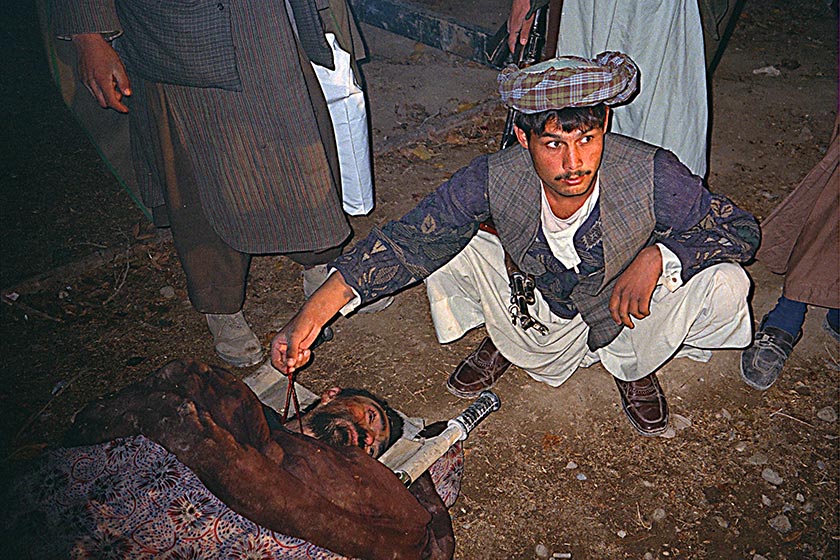

So, first, the Northern Alliance poured gasoline down through a ventilation duct and lit it. Then they poured diesel fuel down there and lit that. Then they dropped rockets and hand grenades, one after another, all afternoon, so many that it became boring. And then they flooded the basement with water, cold water. So much water that dead bodies started floating and the men who were too injured to stand drowned. This was too much for those who were still alive. They began screaming for the Northern Alliance to stop, and then they started coming out, one at a time, until there were 86 of them — wounded, wet, filthy, and insane. That was Saturday afternoon, one week after they had been brought there. The smoke from the fires had killed half of them, and then the water had killed half of those who were left , but the rockets and grenades were relatively ineffective because the walls down there were thick concrete — built by the Russians.

Some were treated by the Red Cross, some were given apples and oranges, all were loaded either into an open flat bed or an enclosed container. This is when a correspondent for Newsweek, Collin Soloway, discovered that one of the prisoners was an American. He was sitting up, leaning on the tail gate of the open truck. His long black hair and beard were caked with dirt and blood and the skin on his face was dark from soot. Suthaway asked him where he was from and he said, “I was born in Washington D.C.”

One of the prisoners died that night in the back of the flatbed, which left eighty-five men alive. If you add eighty-five and 188 and subtract from 400 that means there are still about a hundred bodies in the basement. The smell comes wafting up and rises through the air and the falling snow does nothing to diminish it. Naji is in the cab, honking the horn. He wants out of here. I leave and go back to the hotel and use my toothbrush, an extra one, to clean every bit of mud off my boots in the bathroom sink. I even take out the laces and wash them in my hands.

Qala-i-Jhangi/Sherbigan prison photo gallery

The Hotel

The power is out and there are eight of us in the room of the French television producer. She has three kerosene lamps and keeps her kerosene stove so hot that it glows red. She has pate, and she has vodka, and she has a satellite phone that sits on the floor and is open to anyone who needs to use it.

There’s a knock on the door and she yells, “Come in, don’t bother to knock. . . . Ah, Damien, you are so beautiful, I was looking for you. Please, take off your shoes.”

Damien is an independent cameraman, also French, who’s been trying to leave Afghanistan but has no visa to enter any bordering country. It’s a complicated story and one that’s not uncommon among the journalists here — they came in not worrying about how they were going to get out.

“Damien,” she says, “have some pate, it’s very good. I wanted to tell you that we were at the airport today when the French troops arrived, and as it happens I know their commander. He’s a very good friend of mine. We were together, years ago, in Africa. Anyway, I mentioned that there were some of us who had no way to get home and he offered to let us travel on his planes directly to Paris. What do you think of that?”

“Wonderful,” he says, “you’ve solved all my problems and given me pate.”

Najibullah is sitting next to me on the floor, transfixed, soaking in everything. This is what he lives for, to hang out with westerners and study their ways. He knows everyone and they all like him because he’s usually happy and curious and eager to help. He’s been offered more money than I am paying him, but he’s refused because of his promise to me.

There is another knock on the door and it’s the other Najibullah, the number-one translator in town. He’s an English teacher and wears a wool suit with a tie, a little stiff for this crowd. He enters and takes off his scarf and hat and says, “I have news. The Black Priest Dodullah, he is in Baaaaalllllllkhhhh.” He has a way of torching the last words of certain sentences, either for emphasis or because of a speech impediment. It’s hard to tell. The Taliban mullah Dodullah is in the ancient city of Balkh, only eight miles away. This means that there could be trouble, which would be good for business all around.

The situation in Balkh is that there are somewhere between 200 and 3000 Taliban there who refuse to surrender. Or perhaps there are no Taliban there at all. It’s hard to tell. The Black Priest is a hard-line Taliban leader known for his severe punishments. He swore never to surrender, but then he vanished. It was thought that he was in Kandahar or that he was dead, but now he’s back — or maybe he isn’t. The people of Balkh are mostly Pashtun — which is why Dodullah would take refuge there — and Dostum and his army are mostly Uzbek, and they want not only the Taliban but those who support them. They want their stuff, their money and pick-up trucks and maybe even their land. The advantage of the Pashtuns is that they have governed the region for 300 years. Dostum’s advantage is that he won the war and has an army capable of surrounding the city and then calling in U.S. air strikes.

Every day for the past week there have been at least 150 of Dostum’s soldiers in Balkh. They have three tanks and a couple dozen pickup trucks with large guns and rockets. The first day they were there I asked their commander what was going on and he said they were “cleaning up,” going from house to house, disarming the occupants and looking for Taliban soldiers. I asked him if I could observe the operation, but he said they only do it at night, and so it would not be possible. A correspondent for National Public Radio went there a couple of days later and demanded to see the weapons that had been confiscated and the men who had been taken prisoner, but he was given a long run around and then told that there were no guns or prisoners to be seen. On the same day I was stopped a mile outside of the city because Dostum’s men had shot at a Toyota van and three occupants had been wounded. One guy had been badly hurt and was taken to the hospital in Mazar, another was hit in the foot and was standing outside the van with a crutch, bleeding on the road, and the third guy was in the van with a bandage wrapped around his head, in shock. They were not Taliban, they were Uzbek. It had been a mistake, caused by someone wearing the wrong color of turban.

That’s about as much evidence as we have about what’s going on in Balkh. What needs to be done is for one of us to go there and stay for the night and go out and see what’s happening there — at night. This would no doubt be very scary and cause a large amount of pandemonium, and there are no volunteers. We sit in silence, looking at the kerosene lanterns, wondering if maybe there’s still some more vodka.

The road to: Mazar →Sherbigan →Qala-i-Jhangi →Kabul

A Trip To The Capital City

I’m running out of money but I want to go to Kabul — just to see it and the mountains in between. I ask Najibullah how much it will cost.

“By private car it will take $200, maybe $400.”

“That’s like a year’s wages. There’s got to be a cheaper way or no one would ever go.”

“Yes, there are local cars, like taxis, and for this it is only $50 for both of us there and back, but we can not go by local car.”

“Why”

“Because journalists can only go by private car, and sometimes they take a guard with the Kalashnikov.”

“But that’s not necessary now. Is it? Isn’t it safe to Kabul now?”

“Yes, it’s safe, but we will not get permission to go by local car.”

“Then we won’t ask for permission, we’ll just go.”

“But this will be very bad for me.” He says this in the most forlorn way, as a sad sigh, as if I am asking him to cut off one of his fingers.

“Then I’ll go alone, and that way you won’t get in any trouble.”

“But I must go with you, I promised you that I would not leave your side, and so I can only go where you go. If you want we can ask to go by local car. Maybe they will say yes.”

“But it’s late now and the ministry is closed and I’d like to leave tomorrow morning.”

“We can ask the man here in the hotel.”

“Which man?”

“The man in the office.”

“I thought he was the manager of the hotel.”

“He works for the ministry of foreign affairs.”

“But he’s always here.”

“Yes, because all foreigners are staying here.”

“Then why do you always go across the street to the office to ask permission any time we go somewhere?”

“Because there is another man, a bigger man.”

“Okay, whatever.”

The smaller minister of foreign affairs is in the office sitting next to the wood stove. Najibullah tells him our plans and he asks us to sit down.

“We are asking that all journalists travel to Kabul in private cars with armed guards because we can’t be certain of your safety. It is a long way, and out of our district.”

I think this is bullshit, just a way to squeeze more money out me. But I don’t say this. “It’s very important for my story,” I say, “that I travel in a local car.”

“Aren’t you afraid?”

“No, I’m not. Everyone I’ve met here has been very friendly and helpful. I haven’t had any trouble with anyone, and this is what I would like to write for my magazine, which is read by millions of Americans. I would like to tell them that Afghanistan is a good place and that they should come here on vacation, but how can I say this if I travel with an armed guard? I need to take a local car and travel with other Afghans.”

“But we can’t be sure of your safety.”

“No, but then who can? My fate is in God’s hands, is it not?”

“Yes, certainly. Inshallah.” I had him there.

“Inshallah then, so it’s okay?”

“Yes, we will try it this once, but please if you would send word back with the driver, saying that you have made it safely so we do not worry.”

We leave the hotel just before dawn and take a taxi to the place where the local cars meet. Najibullah tells me to stay in the car while he goes in to buy two tickets. If they see me, he says, they will charge much more for my ticket. He comes back and says, “Okay, let’s go, follow me.” I get out and all the men who are standing around start yelling at once — “Horiji!” “Horiji!” — like they’d never seen a white man.

“Quickly.” Najibullah says, “Please, get inside the car.”

“What are they saying?” I’m sort of fascinated that my presence can cause such excitement.

“Never mind, just get in the car.”

“Tell me what they are saying so I can respond.”

He looks at me with a blank stare for a second and then turns and yells at the crowd and they back off and quiet down.

I get in and he tells me that the men were saying that I am a rich man and it’s not fair that I buy a regular ticket, and they wanted to take something from me. So he told them that I am a very famous writer and that if they didn’t stop bothering me I would tell all Americans that Afghanistan is full of bad men and that nobody should ever come here. It worked. We even have a man with a machine gun standing by the front of the car, on guard, although he’s letting a little kid press his face up against my window and stare, only inches away.

The car is a Toyota Corolla sedan. They fill it with three other passengers and the driver, making six — Najibullah sitting in the middle up front and shifting gears between his legs. We drive east out of the city across the flat desert, skirting the foothills of the Himalayas. I crack my window because it’s steaming up. I look for the mountains but it’s a gray and foggy morning and I can’t see a thing except sand dunes.

After fifty miles the fog has lifted and I can see the base of the mountain wall, impenetrable except for a narrow slit, almost like a vagina. We turn and head straight for it — a narrow canyon only fifty feet wide at bottom, room enough for only a river and a road between vertical cliffs of volcanic rock. This place has a very old name, for sure, but I don’t ask what it is because I want to make up my own. I’m thinking about it when the driver points out the rusted carcass of a Russian helicopter crashed into the cliffs 300 feet above the road. Then he points out the bomb craters in the road — twelve feet wide and six feet deep — and the burned out shells of Toyota pickups off to the side. The Taliban came through here when they fled Mazar and the U.S. planes picked a few of them off, maybe ten trucks and thirty bombs. The driver weaves between the craters and complains that this was a good road before the Americans bombed it, and he wants to know if somebody is going to come and fill in these holes.

“Yes, for sure,” I say. “We have special machines for doing this, they’re called bulldozers, very big and strong, and we have so many that we don’t know what to do with them.” And I make a note in my notebook, a reminder to call the road department upon my return home.

The narrow canyon opens onto a wide, flat valley. It’s circular, thirty to forty miles in diameter, surrounded by mountains, and in the center of the circle is a volcanic plug — the valley is a caldera. The surrounding mountains are smooth and barren, sun-baked dirt, like the skin of an elephant. They’re either heavily over-grazed or they’ve never, ever, had anything growing on them, it’s hard to tell.

“Is it okay if I smoke?” I ask. I’m hungry and because it’s Ramadan there’s little chance that we’ll be stopping to eat.

“Yes, go ahead,” the driver says.

“But is smoking against the rules of Ramadan?”

“Yes, everything is against the rules of Ramadan,” he says. “It is forbidden even to smell a flower, or to look at a beautiful young girl. We can have no pleasures during the day, but at night anything is possible.”

“But it’s okay if I break the rules?”

“For you it is not breaking the rules. You are a Christian and have your own book, and so for you it is not forbidden, am I right?”

“You’re right. In fact Jesus smoked hashish.”

“No, I think this is not true.”

“Well, maybe not, but Mohammed smoked hashish, didn’t he?”

“No, sir, I am telling you that this is not true. Where did you hear this?”

“From a Russian.” I’m making all this up and realize that I’m bordering on rudeness but I want to see how he’ll react. I grew up with religious fanatics, among the Mormons, and I can’t help myself.

“The Russians do not believe in God. You must not listen to what they tell you,” he says, and everybody in the car seems to agree on this.

“Well,” I say, “what about the deal with women. I haven’t seen one woman since I’ve been here who hasn’t been under a burka. Don’t you wish you could look at women, you know, just look at them?” And the driver is stunned by this. A horiji speaking of wanting to see Afghan women is too much of an affront. So Najibullah takes over, trying to smooth things out by telling me that perhaps with the Taliban gone the women will someday take off their burkas, perhaps at the university, but that it’s not such a good thing because these women might be beaten by their husbands or fathers.

“That’s how it used to be,’ I say, “but don’t you think it will change?”

“No,” he says, “it will not change because it’s what we believe. The Taliban believed this, but we also believe it, the Pashtun people.”

“So have you ever gone on a date?”

“What’s a date?”

“Like when you go somewhere with a girl and maybe hold her hand or kiss her.”

“No, I’ve never done this. I’ve never even spoken with a girl other than my sisters. If I speak with a girl in this way then our fathers would beat us with a stick.”

“What if you actually had sex with a girl?”

“Then we would both be beaten many more times and forced to marry each other.”

“What if when you are married, or not you, but someone else is married and his wife has sex with another man?”

“Then she will be killed with the Kalashnikov.”

“Who would kill her?”

“Her father or her brother.”

“I don’t believe that.”

“It’s true, believe me.”

“You would do this? To your own sister?”

“Yes, I would have to, for my family.”

“No,” I say, putting my hand on his shoulder, “Naji, I know you and you wouldn’t kill your own sister. I’m sorry, I wasn’t really serious before, but this is a serious thing. You wouldn’t really kill your own sister.”

“Yes, I would. First it is my father’s responsibility. If he doesn’t do it, then my biggest brother must do it. If not he, then my next smaller brother, and then my next brother, to me, and I’m telling you serious I would do it.” To drive home the point he tells the other men what he’s saying and they all nod their heads, Yes, she must be killed.

“With a Kalashnikov?” I ask.

“Or by putting the stones on top of her,” the driver adds.

From the plain of the caldera the road rises over a low pass and then into a broad canyon, more like a long valley, with pastures and irrigated fields, small villages and the town of Pol-e-Khomri, where there’s a cement factory and an army base built by the Soviets. Beyond the town is the Hindu Kush — snow-covered sawteeth over 15,000 feet high, a natural fortress made from the crashing of India into Asia. Somehow the highway goes up and over these mountains, from the Oxus to the Indus, but it looks impossible.

As it turns out, the ascent is gradual, with switchbacks and avalanche sheds built by the Soviets and marked every mile or so by one of their tanks, parked and abandoned circa 1989, left to rust as monuments. At eight thousand feet there’s snow and ice on the road and our driver gets out and ties on some chains with rope. At nine thousand feet it’s snowing. And then the road ends. We’re at the Salang Tunnel.

The roads ends here because the tunnel was blown up in 1997 by the ethnic Tajik commander Masoud, who was killed in September by Al Queda terrorists impersonating television reporters. Masoud’s troops had been pushed out of Kabul by the Taliban and he bombed the tunnel as a defense. Now cars and trucks cannot enter, but you can walk through — a distance of two kilometers — or you can walk over the Salang Pass — 2,000 feet higher — the old way, in a blizzard. On the other side it’s downhill all the way to Kabul.

At road’s end, men and boys — porters — stand in the snow with bare ankles and plastic slippers. All the cargo on this, one of the oldest and most important roads in the world, has to be carried by hand and on the back through the tunnel. They want to carry my pack and I tell them no. They get upset and grab at it — acting like it’s a union deal and I don’t have a choice in the matter — but I push their arms away and tell them to back off.

“Come quickly,” Najibullah says, “and you must walk exactly where I step. There are still land mines here.” But it seems that he’s exaggerating the risk and maybe freaking out a bit from the alpine conditions.

The north entrance of the tunnel is clear, but inside is a jumble of re-bar and slabs of concrete and sections of ventilation ducts, and we have to turn on our head lamps and move carefully so as to not get jabbed or tripped. And then it gets worse, so that we’re climbing over and ducking under fallen supports, big slabs of concrete hanging down from the ceiling. There are many other people in here — women with little kids crying, porters with huge boxes on their backs, workers or slaves salvaging scraps of metal and huddling around small fires to stay warm — and the air is so full of dust and smoke that every flashlight makes a distinct cone that fades into darkness. It’s creepy, apocalyptic, and bad for your lungs. It takes an hour to get through, moving as fast as we can go without running.

The south portal has been blown apart so that we have to climb over a tall and icy mound of debris, then we’re out. It’s still snowing, although there’s no wind on this side. Just beyond the portal are more taxis and trucks, along with another crowd of men. I walk up and they all start yelling, making noise like a swarm of angry bees. They try to surround me, they try to block me, but I keep walking. I’m not worried — I’m much larger than they are, and they’re wearing those plastic slippers — but I am amazed by the barrage of shouting, they’re so excitable. Najibullah finds a car going to Kabul and tells me to get in.

“What were they saying?” I ask.

“When you came out of the tunnel they were saying that you were a foreigner and that you were alone and that they should take your money and kill you.”

“But they didn’t have any guns.”

“Yes, they have guns. And knives, like this,” he said, pulling out a four-inch stiletto. “They hide them.”

“Naji,” I say, “put that away. No one’s going to mess with us.”

“Okay, but please stay in the car.”

Again there are six of us in a Toyota Corolla and the driver speeds down the mountain, hurrying to get to Kabul before dark. Three times we cross the river in the bottom of the canyon and at each crossing there’s a concrete bridge that was blown up by Masoud’s troops. In place of the larger concrete bridges they’ve made smaller bridges down close to the water by piling up big mounds of dirt, sometimes using Russian tanks for buttresses, and spanning the distance with metal planks that look like dismembered pieces of tank frames. Nothing larger than a small truck can pass over these bridges, and none faster than a breathless crawl.

We arrive at the edge of Kabul at dusk. It feels like being in a crater where the bomb exploded a long time ago but the dust has still not settled. The road into the city is lined by shipping containers, side to side, continuous, filled with scraps of metal and fire wood and dark dusty stuff like car wheels and motorcycle frames and doors. In front of the containers men stand around and work, pounding metal or cutting wood or fixing horse carts or cutting up empty cans. Our driver is swimming through traffic — honking, stopping, going. I ask Najibullah a question just as the guy on the other side of the back seat says something to him. I say, “Hey, do these people live in those containers?” but Naji chooses to translate for the other guy. “This man thinks you have a very beautiful face and he would like to give his love to you.” No one laughs. No one thinks this is funny except for me, and I let the comment fade with the light.

“Would you like some tea and bread?” he asks, carefully separating each word and rolling the r in bread.

“Yes, thank you.”

“In Afghanistan we give our guests everything. While you are in my house whatever you need you have.” He’s beaming at me like I am a rare jewel, and three of his little children are climbing over each other holding themselves back from petting me like a new puppy.

I’ve been told that Afghans consider themselves to be the ultimate hosts, that once you are in their home they will die trying to protect you from your enemies. This may be true, but at the same time they won’t let you meet or even look at their women.

“What was it like when the U.S. was bombing the city?” I ask. “Did bombs fall close to here?”

“Yes, every night, some only five or six blocks from here. Big bombs, very big bombs. I could not sleep, my children were very afraid.”

“Did the bombs kill civilians or did they hit military targets/”

“They hit the military targets, but some civilians were died.”

“How many?”

“I think 100 or 150.”

“And is that a lot or not that many?”

“I think it is not that many. We are very happy that the Taliban are finished. I am engineer, but I have no work for four years. I work only some days as chauffeur. I want very much to work for my family.”

“What do you think America should do to help?”

“America should give peacekeeping force here to take guns. There are many, many guns, and there are many fighting for Afghan people. If America or United Nations peacekeeping force do not come here then it will be very bad, worse than before the Taliban. But they will come, it is true?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “Maybe not.” I don’t want to lie to him.

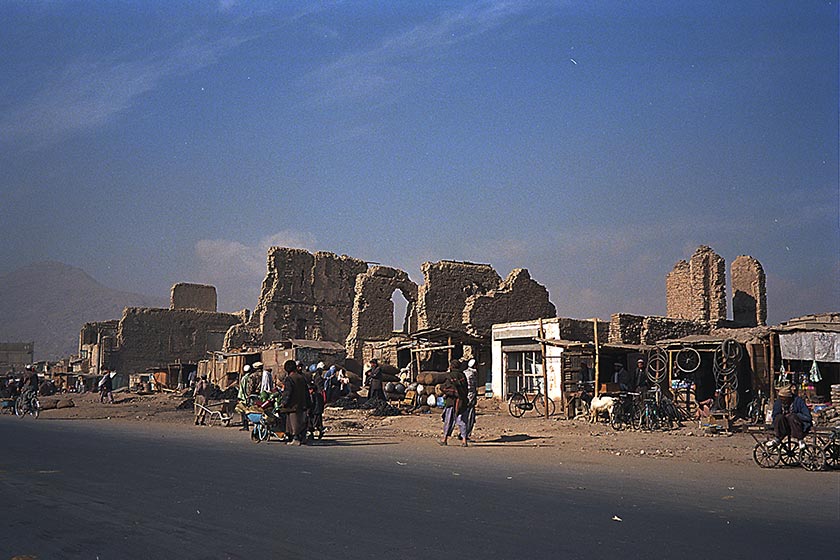

The next morning another uncle of Najibullah’s drives us around the city in his taxi cab. We go by the lamp post where the Taliban hung the body of President Najibullah. We drive by the soccer stadium where the Taliban conducted public executions. Then we go to the zoo, which has been bombarded by mortar shells. There are a lot of empty cages with big holes in the walls, but there are still some animals alive — monkeys, hawks and eagles and vultures, and a lion that looks senile or dazed and is missing an eye. Near some of the cages is a shipping container riddled with bullet holes and blown up from the inside out — it’s square metal doors shredded and its walls were puffed out, sort of spherical. It’s empty, sitting by itself, like a piece of sculpture.

Beyond the container is the Kabul river, which after three years of drought is not much more than a series of festering pools. Still, there are people using the water — bathing in it, drinking it, and filling buckets to wash taxi cabs. We exit the zoo into an entire neighborhood that has been demolished by bombardments — acres and acres of adobe ruins.

“What happened here?” I asked Naji.

“It was the Hazara people who were living here and Masoud’s army shelled them from that hill.”

“Why?”

“Because they are Hazara people and Masoud’s people are Tajik.”

“This was before the Taliban took over?”

“Yes, when the Taliban came they stopped this fighting.”

“What a fucking mess,” I say. “I’m sorry.”

“How long would it take in America to rebuild this place?” Naji asks.

“Oh, shit, in America it might take three years.”

“And then it would be as good as Tashkent?”

“Well,” I say, “anyplace in America is a lot better than Tashkent. But it’s not going to happen like that, I don’t think. Maybe America will give Afghanistan some money for rebuilding, but the work will probably have to be done by the Afghan people.”

“And how long will that take?”

“I don’t know, maybe fifty years.”

“But I will be an old man by then.”

“Yeah, you would be. My advice to you is to try to find a way to get out of here.”

“Where will I go?”

“Anywhere. The world is a big place and there are a lot of things to see. A lot of opportunities.”

“But I think this is not possible for me.”

I don’t know what to tell him. If his family had any money they would have left years ago, along with the rest of the middle class. The only people left in Afghanistan are poor and have no modern skills. It will take a long time, maybe forever, to make this place look even as good as Tashkent, and then it will still suck.

Naji just looks at the ground and kicks a brick and says, “Shit.”