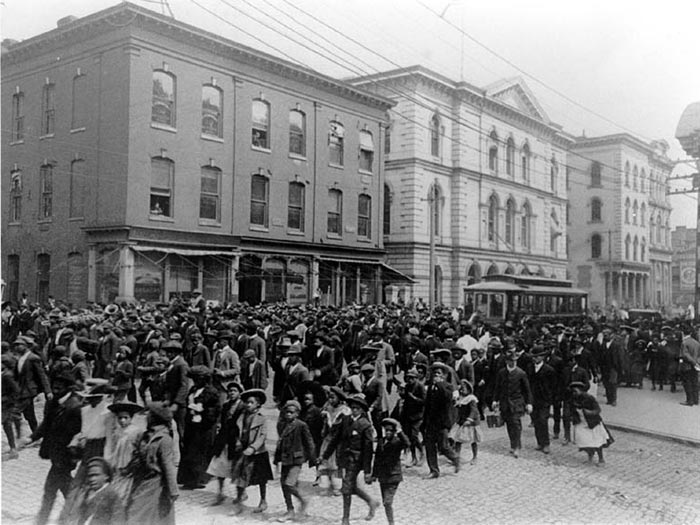

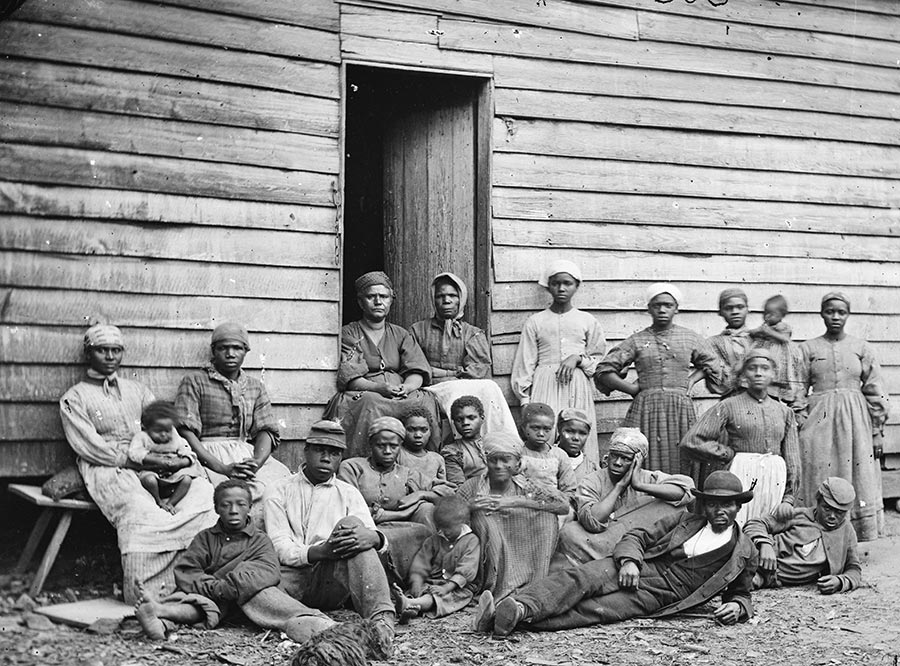

Juneteenth: Emancipation

Juneteenth celebration, Emancipation Day, in Texas, June 19 1900

Below are edited interviews from “Voices from the Days of Slavery”, an online exhibition of the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress.

The collection houses a history rarely heard first-hand: audio interviews with former slaves, sharing their life stories, before, during, and after slavery.

Mrs. Laura Smalley: Mama and them didn’t know where to go, you see after freedom broke. Just turned, just like you turn something out, turned us out just like, you know, you turn out cattle. [laugh]

John Henry Faulk: You remember when the Civil War was being fought?

Mrs. Laura Smalley: Well, I, I can’t remember much about it, but I remember this much: Mr. Bethany, was gone a long time. And I remember all the next morning, we all got up and all of them went to the house. Went to the house to see old master. And I thought old master was dead, but he wasn’t. He had been off to the war, and ah, come back. But then I didn’t know, you know, until the war. I just know he was gone a long time. All them Negros gather ’round and see ol’ master again.

John Henry Faulk: Well, c an you remember what happened when they set you free? Do you remember how the old master acted …

Mrs. Laura Smalley: No, sir. I can’t remember that, you know. But I, I remember, you know, the time they give them a big dinner, you know on the nineteenth.

John Henry Faulk: Is that right?

Mrs. Laura Smalley: On, on the nineteenth, you know. They give them a big dinner.

Well now, we didn’t know . I don’t hide the other side of the folks know, freedom. We didn’t know. They just thought, you know, were just feeding us, you know. Just had a long table. And just had ah, just a little of everything you want to eat, you know. And drink, you know. And they say that was on the nineteenth. Well you see I didn’t know what that was for. Now a child 6-7 years old can tell you.

John Henry Faulk: That’s Right.

Mrs. Laura Smalley: You know, and old master didn’t tell you know, they was free.

John Henry Faulk: He didn’t tell you that?

Mrs. Laura Smalley: No he didn’t tell. They worked there, I think now they say they worked them, six months after that. Six months. And turn them loose on the nineteenth of June. That’s why, you know, we celebrate that day. Colored folks, celebrate that day.

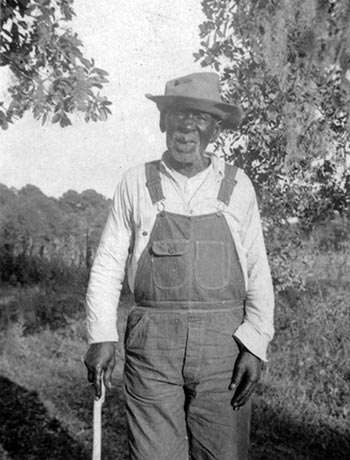

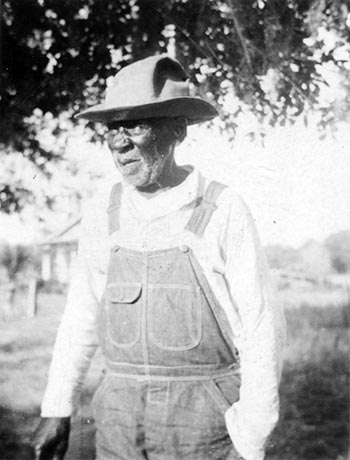

Elmer Sparks: The following is an interview between Elmer Sparks, Texas ranchman and historian, and, with Charlie Smith, old-time slave of Bartow, Florida.Charlie Smith

Charlie Smith: I was born in Africa, Liberia, Africa. And come to the United States. That was in slavery time. They sold the colored people. And they brought me from Africa. I was a child, a boy.

Elmer Sparks: Did they trick you to get you on the boat?

Charlie Smith: What? They fool you on the boat. They fool the colored people on the boat. They say, “Over in that country, you don’t have to work. If you get hungry, all you got to do go to the fritter tree.” Same thing now, people call them pancakes, they call them flitters. Had the fritter tree on the boat. Then he show us the syrup tree. “Come on down here!” And the hole on the lower deck on the boat, they called the hatch hole. “Come on down here in the hatch hole.” Got down in the hatch hole, we should have felt the boat moving. And they are leaving. And when it landed, it landed in New Orleans.

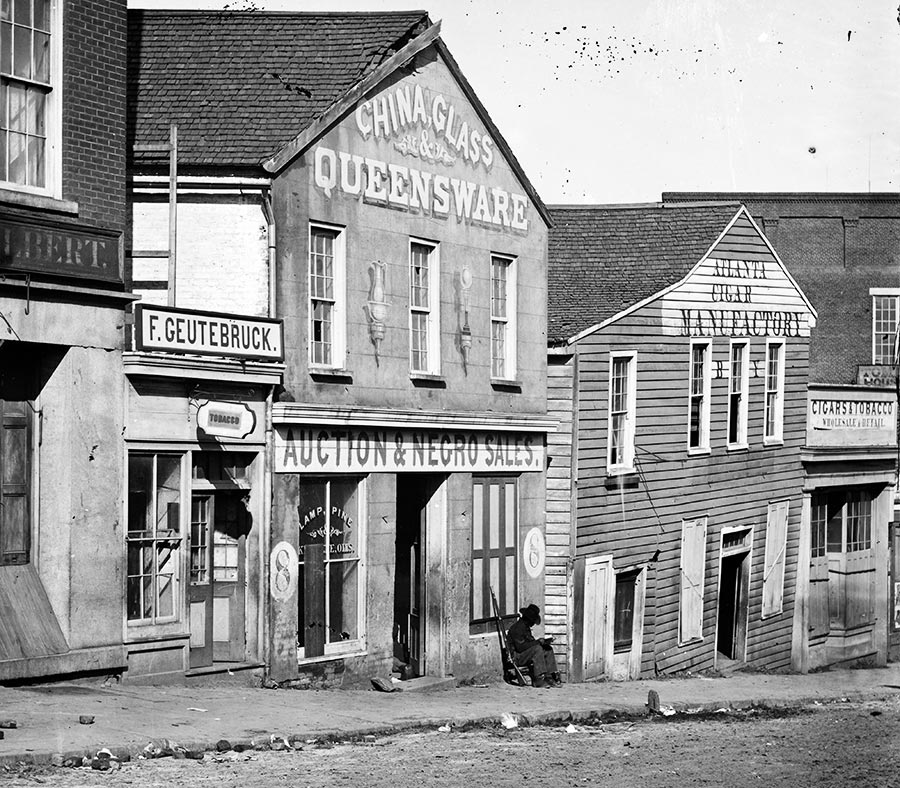

The ,man, they put you up on a block. They sell you; they bid you off. The highest bidder gets you. He’ll carry you to his plantation. And they went to mistreating the, the colored. Getting children by the colored women.

And they come down, the North and the South fought a war to free the colored. North and South fought a war to free the colored people from slavery time.

Fountain Hughes: My name is Fountain Hughes. I was born in Charlottesville, Virginia. My grandfather belong to Thomas Jefferson. My grandfather was a hundred and fifteen years old when he died. And now I am one hundred and one year old.Fountain Hughes

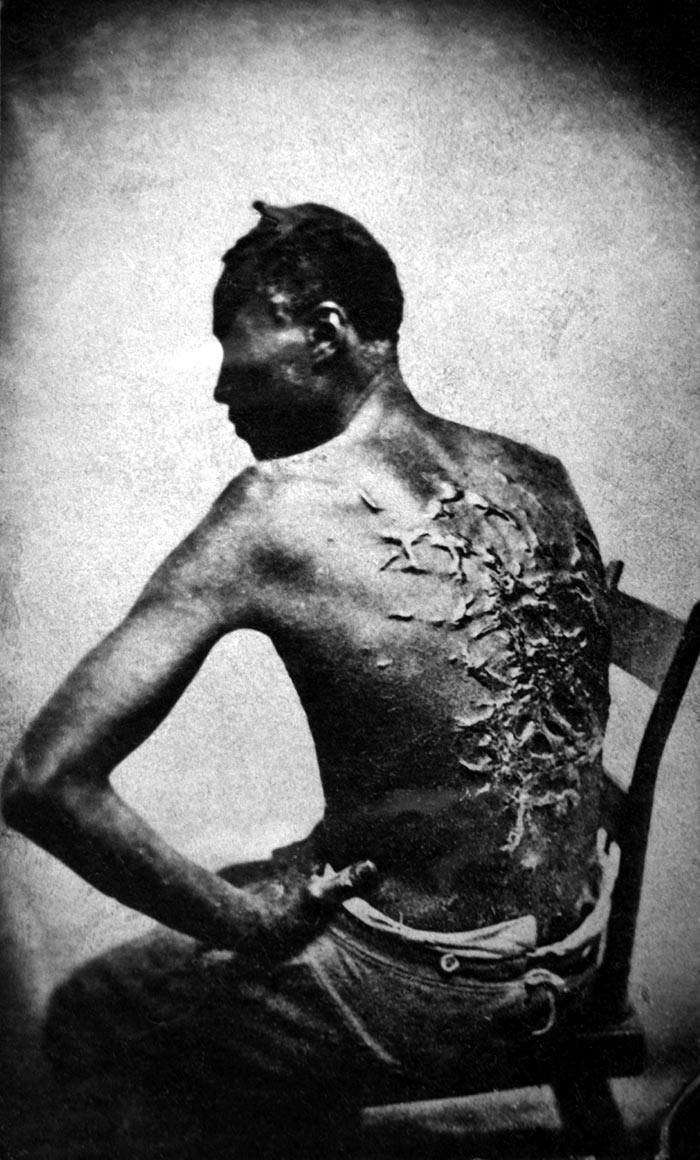

To tell you the truth, when I think of it today, I don’t know how I made it. You wasn’t treated as good and they treat dogs now. But I don’t like to talk about it, because it makes people feel bad.

Hermond Norwood: Do you remember much about the Civil War?

Fountain Hughes: I remember when the Yankees come along and took all the good horses and took throwed all the meat and flour and sugar and stuff out in the river and let it go down the river. And they knowed the people wouldn’t have nothing to live on, but they done that. And that’s the reason that I don’t like to talk about it.

Colored people is free, and they ought to be awful thankful. And some of them is sorry they are free now. Some of them now would rather be slaves.

Hermond Norwood: Which would you like to be, Uncle Fountain?

Fountain Hughes: Me? You know if I thought, had any idea, that I’d ever be a slave again, I’d take a gun and just end it all right away. Because you’re nothing but a dog.

Aunt Phoebe Boyd: that day is coming. That day is coming. That day is coming and we got to prepare that day.

They gave us, commandments, Lord. I want to hear the first trumpet when it blows that morning. He, gave us commandments, Lord. They gave us Christ, went down Jerusalem. Mount Dry Bone.

The interviewees were mostly near 100 years old. The interviews were recorded mostly in the 1930s and 40s. But even when the audio quality isn’t good, the quality of these American citizens’ character comes thru, especially as they broke into prayers and songs.

The interviewers included the Lomax family, John and Runby, and their son Alan, all pioneering field-recordists who documented much of early Americana music. Writer Zora Neale Hurston was also an Another interviewer. While collecting Gullah songs on the Sea Islands of Georgia in 1935, she recorded one of the singers, former slave Wallace Quarterman.

Zora Neale Hurston: After they said you can go free, then what did you do? Did you leave the plantation that day after they told you to go free?

Wallace Quarterman: After the sword was down, so was the tension, in the South tension. And then they play. and he said to them the Yankee [beat to the landing the drum (?)]. Way Down South getting mighty poor. Say they, used to drink coffee but now they drinking rye. They said let the Union Band make the rebel understand. To leave our land for the sake of Uncle Sam.

I ain’t going anywhere. I’ve been to war already.

Many of these recordings were made as part depression-era jobs programs, like the Federal Writers’ Project and Works Progress Administration. Even though the country was broke, we somehow managed to send people across the county, field-recording what Amercians were saying, singing, and doing. I wonder: Now that we can afford it, we have no national program field-recording program. What vital parts of present history are we losing?

John Henry Faulk: Can you remember slavery days very well?

Harriet Smith: Of course. I can remember all our white folks. And all the names of them, all the children.

John Henry Faulk: Who, who did you belong to?

Harriet Smith: J. B., the baby boy.

John Henry Faulk: How many slaves did he have?

Harriet Smith: Well, he had my grandma, and my ma was the cook,My ma was the cook, and grandma, you know, and them they worked in the field, and everything. I remember when she used to plow oxen. I plowed oxen myself. I can plow and lay off a corn row as good as any man. Chop, and chop, pick cotton, pick my five hundred pounds of cotton. Then walk across the field and, and hunt watermelons, pomegranates [laughs].

John Henry Faulk: Well, well, while you all were slaves did they teach you to read and write?

Harriet Smith: Nuh huh.

John Henry Faulk: Did you all go to school any?

Harriet Smith: Nuh huh. They didn’t know nothing about reading and writing. All that I knowed they teach you is mind your master and your mistress.

John Henry Faulk: They sure didn’t teach you any reading and writing?

Harriet Smith: No, they didn’t. No. I remember then picking cotton. Yeah, I remember all about those slivery times.

- Voices from the Days of Slavery (LOC)

- Juneteenth (Wikipedia)

- Fountain Hughes: Wikipedia | U of VA | NY Times | Monticello | PBS

- John Henry Faulk: Wikipedia | LOC| NY Times | NPR

- Charlie Smith (Wikipedia)

- Slavery in the United_States (Wikipedia)

- Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery (Gutenberg)

- Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project (LOC)

- From Slavery to Freedom: The African-American Pamphlet Collection (LOC)

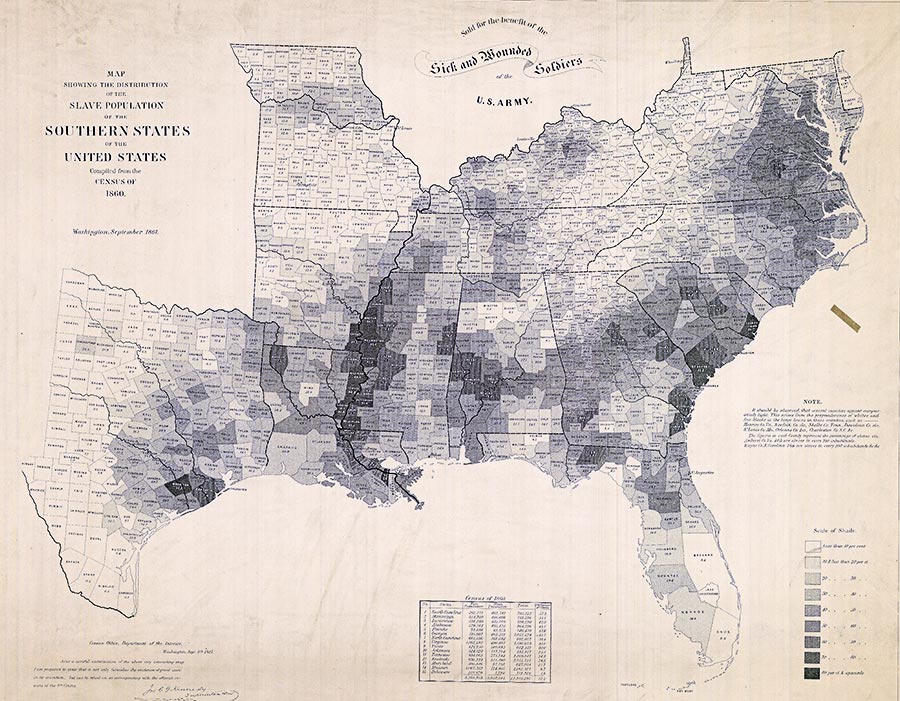

- A Map of American Slavery (NY Times)