HV/Series/Episode/ Work by: Joe Frank · Harry Shearer · Jean Shepherd · Art Silverman

![]() Hearing Voices from NPR®

Hearing Voices from NPR®

067 Jean Shepherd 1: A Voice in the Night

Host: Harry Shearer of Le Show

Airs week of: 2010-07-14 (Originally: 2009-08-12)

“Jean Shepherd 1” (52:00 mp3):

Hour one in this two-part tribute to radio raconteur Jean Shepherd:

Jean Shepherd used words like a jazz musician uses notes, winding around a theme, playing with variations, sending fresh self-reflective storylines out into the night. Marshall McLuhan called Shepherd “the first radio novelist.” From 1956-1977 Shep spun his late night stories over WOR radio, New York City. PBS gave him a TV series, “Jean Shepherd’s America.” In 1983 he co-wrote and narrated the film version of his “A Christmas Story.”

Shep inspired a new generation of spoken narrative artists who tap into the American psyche. Among them was Harry Shearer (Le Show), who hosts this two part tribute to Jean Shepherd. Shearer interviews Shep’s co-workers, friends and fans, including Robert Krulwich, Joe Frank, Paul Krassner, and Jules Fieffer.

Thanks to Mr. Shearer, KCRW– Santa Monica (and Sarah Spitz), NPR, and Art Silverman for production support, and for allowing us to re-air this two-hour tribute. This is part one; part two is next week.

One time I woke up at 3 o’clock in the morning. My radio was still on, and a man was talking about how you would try to explain the function of an amusement park to visitors from Venus. It was Jean Shepherd. He was on WOR from midnight to 5:30 every night, mixing childhood reminiscence with contemporary critiques, peppered with such characters as the man who could taste an ice cube and tell you the brand name of the refrigerator it came from and the year of manufacture. Shepherd would orchestrate his colorful tales with music ranging from “The Stars and Stripes Forever” to Bessie Smith singing “Empty Bed Blues.”

–Paul Krassner (from “How the Realist popped America’s cherry“)

The Realist: series of Jean Shepherd essays, Radio Free America, issue #42, #44, #48, #50.

Jean Shepherd – The Great American Fourth of July – PART 1

Dialing through the AM whine and static, I landed upon the chuckling voice of a man who immediately sounded to me like the aural personification of what was, up until that moment, my bible of irreverent, hip “outsider-ness”— Mad Magazine! Suddenly, there in the dark, I found myself in the presence of a grownup who not only used words like “clod,” but actually talked about “kidhood” with such accuracy that my fevered 11-year-old brain immediately sensed a kindred spirit! That’s all it took — one tale about Flick, Schwartz, Randy and Ralph — kids just like kids I knew! — growing up in a Midwestern steel town under the weary beer-soaked gaze of “The Old Man”… and I was hooked!

–Vin Scelsa, WNEW- NYC (from WFMU “Excelsior, You Fatheads!“)

Fan sites: Flick Lives | WFMU | Shep Bibliography.

10:15 P.M. The WOR news and weather are out of the way. A bugle sounds, and a sprightly theme song comes trotting on the air. The theme has a double meaning: it is the one that calls the horses to the gate at Aqueduct, and it is the Bahn Frei Overture, composed for an operetta by Eduard Strauss, the only member of the Strauss family who did not make good. Presently, Shepherd’s clear, rowdy voice intrudes. “Okay, gang are you ready to play radio? Are you ready to shuffle off the mortal coil of mediocrity? I am if you are.” There is a noise like a mechanized Bronx cheer (BRRAPP!)— it is Shepherd blowing his kazoo. At other times he twangs his Jew’s-harp (BRROING!). “Yes, you fatheads out there in the darkness, you losers in the Sargasso Sea of existence, take heart, because WOR, in its never ending crusade of public service, is once again proud to bring you — (EROICA SYMPHONY UP) — The Jean Shepherd Program!”

–Edward Grossman, “Jean Shepherd: Radio’s Noble Savage” Harper’s Magazine Jan 1966

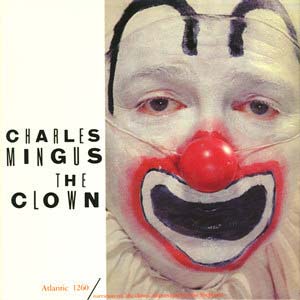

Jean Shepherd’s improvised lyrics to the title track of Charles Mingus’ 1958 The Clown:

Jean Shepherd’s improvised lyrics to the title track of Charles Mingus’ 1958 The Clown:

Man, there was this clown. And he was a real happy guy, a real happy guy.

He had all these greens and all these yellows and all these oranges bubbling around inside of him, and he had just one thing he wanted in this world. He just wanted to make people laugh – that’s all he wanted out of this world. He was a real happy guy.

Let me tell you about this clown. He used to raise a sweat every night out on that stage, he just wouldn’t stop. That’s how hard he worked. He was tryin’ to make people laugh. He used to have this cute little gimmick where he had a seal follow him up and down a step ladder, blowin’ “Columbia the Gem of the Ocean” on a B-flat Sears Roebuck model 1322-A plastic bugle – a real cute act. But they didn’t laugh.

Oh you know, a few little… things… here and there, but not really. And he was booking out on all these tank towns, playing the Rotary Club and the Kiwanis Club and the American Legion hall, and he just wasn’t making it. And he had all these wonderful things going on inside of him, all these greens and yellows, and all these oranges. He was a real happy guy, and all he wanted to do was make people laugh. That’s all he wanted out of this world, was to make people laugh.

And then something began to grow, something that just wasn’t good began to grow inside of this guy…

You know it’s a funny thing. Something began to trouble this clown… you know, little things… little things once in a while would happen that would make that crowd begin to move. But they were never the right things.

Like for example that time the seal got sick on the stage, all over the stage, the crowd just… just broke up. Little things like that, and they weren’t supposed to be in the act, and they weren’t supposed to be funny. This began to trouble him and this began to bother him, this little thing began to grow inside. All those greens and all those oranges and all those yellows… they just weren’t as bright as they used to be. And all he wanted to do was to make that crowd laugh. That’s all he wanted to do.

There was this one night in Dubuque when he was playing this Rotary Club. All these dentists and all these druggists, all these postmen sitting around, and they were a real cold bunch – nothing was happening. He was leaving the stage when he stumbled over his ladder and fell flat on his face, just flat on his face, and he stands up and he’s got this bloody nose and he looks out at the crowd and that crowd is just rollin’ on the floor – he’s knocked ’em flat out. This begins to trouble him even more. And he sees something – he begins to see something… hmmm?

And right about here things began to change, but really change. Not the least of which, our clown changed his act. Bought himself a set of football pads, a yellow helmet with red stripes, hired a girl who dropped a five-pound sack of flour on his head every night from maybe twenty feet up. Oh man, what a bit! That just broke them up every night – but not like Dubuque!

And all those colors? All those yellows, all those reds, all those oranges? A lot of gray in there now, a lot of blue. And all he wanted to do was to make this crowd laugh, that’s all he wanted out of this world. They were laughing all right. Not like Dubuque, but… they were laughing.

And the dough started to come in, and he was playing the big towns, Chicago, Detroit…. And then it was Pittsburgh one night – real fine town, Pittsburgh, you know. About three quarters of the way through his act, a rope broke. Down came the backdrop, right on the back of the neck, and he went flat. And something broke. This was it. It hurt way down deep inside.

He tried to get up. He looked out at the audience and man you should… man you should have seen that crowd – they was rollin’ in the aisles! This was bigger than Dubuque!

This was bigger than Dubuque! He really had ’em going…

This was it. This was the last one. This was the last one. This was the last one. He knew now. Man he really knew now. But it was too late. And all he wanted to do was make this crowd laugh – well, they were laughing. But now he knew.

That was the end of the clown. And you should have seen the bookings coming. Man, his agent was on the phone for twenty-four hours. The Palladium… MCA… William Morris. But it was too late.

He really knew now, He really knew.

He really knew now…

William Morris sends regrets.

Jean Shepherd, born/raised Hammond, Indiana:

While the South has been drenched with Decadence, the Midwest has been swimming in a turgid sea of Futility. It is dotted with cities and towns that have never quite made it… The city is too close to the farm, while beyond the last Burma Shave sign the prairie rolls flat as a tabletop endlessly to the horizon. Everywhere are evidences of faded ambitions and forlorn whistles in the dark… It is this incongruity that produces men who are compelled by secret dark inner urges to warn of the futility of the sad earthly posturing of Man. Of these there are two very common Midwestern types: the Humorist and the hellfire fundamentalist Evangelist… Ade himself pointed out in an essay on Indiana that humorists of the nonprofessional but practicing variety can be found every few feet along Main Street… Almost all of their humor is of the school of Futility… Futility, and the usual triumph of evil over good. Which is another name for realism.

–Jean Shepherd, from intro to The America of George Ade

Time magazine: “That Old Feeling: Shepherd and His Flock” | “The Heyday and Dark Nights of Radio Legend Jean Shepherd“.