“From the opening moments, “Cowboy” seizes the heart and soul of the listener for an extraordinary hour. Josh Darsa’s strong story vision and great writing, combined with John Widoff’s brilliantly clear and intimately warm recordings and mix, produced a radio experience that remains unequaled to this day. Listen to “Cowboy” and think about what went into it: planning, attention to detail, patience, and the faith and confidence that the highest standards are both achievable and worth all the work they require. A masterpiece that has endured for decades already, and surely will for many more.”

–Alex Chadwick, June 1998“This was the height of my career at NPR. It was a combination of everything… the music recording, the production sound recording, interviews… every single thing that I had ever done for this company all came together in this show. This was probably how Walt Disney felt when he made Mary Poppins. It was a dream come true for me to build something like this. ‘Cowboy’ is the kind of show you would listen to in a darkened movie theatre. The writing is spectacular.”

–John Widoff, May 1998

NPR.org: ‘Cowboy,’ a Study in Radio Tale-Telling

Hearing Voices episode: “Cowboy”

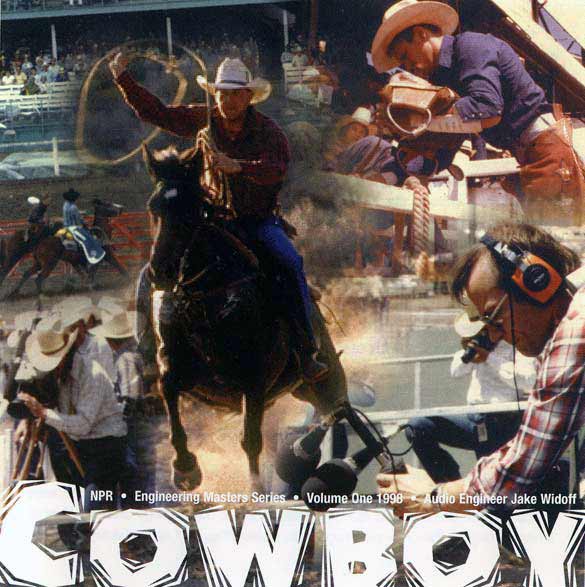

[The following liner notes are from the 1998 CD of “Cowboy,” Volume 1 in the NPR Engineering Master Series:]

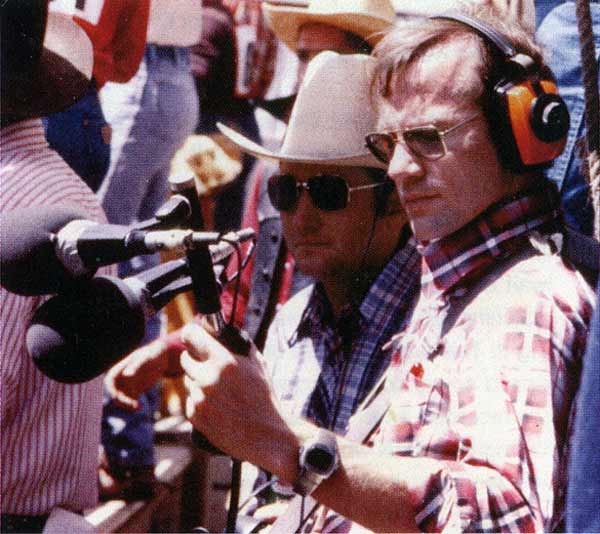

In 1980, journalist-producer Josh Darsa, technical director and recording engineer John Widoff, assisted by Miles Smith, Dave Glasser and shop technician Bob Butcher, collaborated on Cowboy, a project that has become a classic of radio journalism. Cowboy was originally broadcast on October 4, 1980 on a series called The Mind’s Eye. In an interview with Mike Starling, Vice President of NPR Engineering, John Widoff describes their unique effort.

Mega Decks, Mega Mics, Mega Mix

JW: While we were at the rodeo, Josh Darsa wanted to record multiple vantage points of a single scene. For instance, I’d have a Nagra tape recorder on the roof of the grandstand and Miles Smith, a freelancer out of New York (currently Boston), would have a Nagra in the chutes where the riders would bust out for their ride. Then we would have a freeorunning Nagra III on the rodeo announcer. We ran them in sync kinda like you would do in video with multiple cameras. This gave us three different vantage points. During the show you hear the perspective change through cross fading which is a result of these different but simultaneous perspectives.

In gathering the sound, we used every mic technique we could think of… spaced omnis for the big sounds (jets, Happy Jack Road, cars going by, even coyotes); Blumlein; the SM69 in X/Y for the cattle around the truck, etc.

In gathering the sound, we used every mic technique we could think of… spaced omnis for the big sounds (jets, Happy Jack Road, cars going by, even coyotes); Blumlein; the SM69 in X/Y for the cattle around the truck, etc.

There must have been 70 hours or more of tape we shot out there in Cheyenne and every single thing got dubbed. What you heard in the halls of the old NPR were rodeo sounds coming from RC1. Constant horses, bulls, things crashing, just all kinds of things. I think it drove people nuts hearing this stuff up and down the halls.

For the mix, we had the master tape recorder tweaked for 15 i.p.s and the individual playback machines at 7.5 i.p.s (I didn’t want to be running tape on a machine that it wasn’t aligned the right speed for, and with the Scullys it was either/or). We didn’t have multitrack which meant we had to prepare all the material for a multimachine mix. I had to cut and splice all the tape using the spaced leader for timing. This was very time consuming.

I originally used Dolby A noise reduction on the production master and Dolby A on Josh’s tracks but I didn’t like the sound of Dolby A used twice; it just sounded muddy. Kinda like going through analog-to-digital converters too many times. So we rolled the master with no noise reduction to Ampex 456 tape stock on what we called the “Cowboy Scully.” Bob Butcher tweaked that Cowboy Scully and really got the machine to sound great with the 456 at 15 i.p.s. All the Nagra field recording was made without noise reduction. The Aaron Copland music heard in Cowboy came from original Columbia Records masters dubbed to 15 i.p.s Dolby A.

Writing to the Music and Other Trade Secrets

In a movie, a score will be written to the dialogue and the story. For Cowboy, we did the opposite. Josh would listen to the music over and over and write his narrative to it. What Josh wrote is completely inspired by the music. That is why the pauses in the music work so well with his narrative.

We did get into some spots where we did not know how to get out of the music. Everything’s rolling right along but how do we get out of it? One solution: something called the Braun Cut (named after its discoverer Peter Leonard Braun, then, head of the Features Department at Radio Free Berlin). It’s like in a movie where you do something abrupt with one production element to disguise a transition into another. For example, in Cowboy we didn’t want the music to fade out — that would make it sound dumb. Instead, we decided that if the music slammed into something, like the sound of a belt tightening, it could disappear without the listener noticing. So that’s what we did.

Sometimes Josh’s tracks would be moving along with the music, but in order to hit the musical post we needed to somehow jump to a different part of the music without it sounding abrupt. For example, towards the beginning of Cowboy you hear a car passing in the night, and as the car goes swishing by, it drowns out the music. But then, as the car drives off in the distance, the music reappears as though it never went away. That is how we got to a different section of the music so it posted where we wanted it to. We created a diversion and pulled some trickery.

Other tricks included creating the effect of the wind. We were stalled for two hours in the old Studio 2 (before it was renovated). I told Josh we needed the sound of the wind but not from a sound effects record because that didn’t sound right. I was just sitting there staring at the Spectrasonic console and I looked at the module that had the 400 Hz tone, 12K, and white noise. And I said “Whoa, wait a minute, let me do something here.” I got access to the white noise by patching out of the module and put in a Urei Notch filter and started phase shifting it. This was recorded onto a Scully 280B tape recorder which had variable speed so we could manipulate it in that way. We then off-set it because I think we recorded it too fast and took the play-back off the left channel and put it in the right channel which made it stereo (we didn’t have digital effects back then). We recorded it as fast as we could so we could get just the right sound.

We diddled with it, I started running it through the notch filter to give it the sweeping sound, and Josh said “That’s it! Whatever you are doing, that’s what we are using.” We got it after two hours of being stuck, not knowing what to do.

When we were making Cowboy, I thought of myself as a ghost assistant producer as well as a TD. We had a lot of fun making Cowboy. This was the height of my career at NPR. It was a combination of everything… the music recording, the production sound recording, interviews… every single thing I had ever done for this company all came together in this show. This was probably how Walt Disney felt when he made Mary Poppins. It was a dream come true for me to build something like this. Cowboy is the kind of show you would listen to in a darkened movie theater. The writing is spectacular.

–John Widoff, May 1998

Leave a comment: