![]() Hearing Voices from NPR®

Hearing Voices from NPR®

132 Musicality of Speech: Spoken Melody

Host: Barrett Golding of Hearing Voices

Airs week of: 2012-02-15

This program contains copyrighted material not licensed for web-streaming, so we cannot offer an mp3 of this week’s episode.

A history of what composer Steve Reich calls speech-melodies:

“Come Out” (1966 / 3:00 excerpt) Steve Reich

“It’s Gonna Rain” was composed in San Francisco in January 1965. The voice belongs to a young black Pentecostal preacher who called himself Brother Walter. I recorded him along with the pigeons and traffic one Sunday afternoon in Union Square in downtown San Francisco. Later at home I started playing with tape loops of his voice and, by accident, discovered the process of letting two identical loops go gradually out of phase with each other.

In the first part of the piece the two loops are lined up in unison, gradually move completely out of phase with each other, and then slowly move back to unison. In the second part two much longer loops gradually begin to go out of phase with each other. This two-voice relationship is then doubled to four with two voices going out of phase with the other two. Finally the process moves to eight voices and the effect is a kind of controlled chaos, which may be appropriate to the subject matter – the end of the world.

“It’s Gonna Rain” is the first piece ever to use the process of gradually shifting phase relations between two or more identical repeating patterns. The second was “Come Out.” Composed in 1966, it was originally part of a benefit presented at Town Hall in New York City for the retrial, with lawyers of their own choosing, of the six boys arrested for murder during the Harlem riots of 1964. The voice is that of Daniel Hamm, now acquitted and then 19, describing a beating he took in Harlem’s 28th precinct station. The police were about to take the boys out to be “cleaned up” and were only taking those that were visibly bleeding. Since Hamm had no actual open bleeding he proceeded to squeeze open a bruise on his leg so that he would be taken to the hospital.

“I had to like open the bruise up and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them.”

Come Out is composed of a single loop recorded on both channels. First the loop is in unison with itself. As it begins to go out of phase a slowly increasing reverberation is heard. This gradually passes into a canon or round for two voices, then four voices and finally eight.

By using recorded speech as a source of electronic or tape music, speech-melody and meaning are presented as they naturally occur. By not altering its pitch or timbre, one keeps the original emotional power that speech has while intensifying its melody and meaning through repetition and rhythm. During the early sixties I was interested in the poetry of William Carlos Williams, Charles Olsen, and Robert Creeley, and tried, from time to time, to set their poems to music, always without success. The failure was due to the fact that this poetry is rooted in American speech rhythms, and to “set” poems like this to music with a fixed meter is to destroy that speech quality. (Later, in 1984, I was to succeed at last with Williams in The Desert Music by using flexible constantly changing meters.) Using actual recordings of speech for tape pieces was my solution, at that time, to the problem of how to make vocal music.

—Steve Reich, liner notes for Steve Reich: Early Works

Remix of various Steve Reich works, including “Come Out,” “It’s Gonna Rain,” “Marimba,” and “Electric Counterpoint – 2. Slow” (guitar: Pat Matheny), off the CD Reich Remixed.

In this segment from Radiolab’s “Musical Language” episode, host Jad Abumrad talks with Diana Deutsch, a professor specializing in the Psychology of Music and a documenter of Audio Illusions. They discuss her CD Phantom Words and Other Curiosities; in particular, the cut “Sometimes Behave So Strangely:

This CD has featured a number of curiosities concerning speech, and also concerning music. Finally, we examine the mysterious no-man’s-land between the two, and show how fragile the boundary between them can be. Composers throughout the ages – Monteverdi, Mussorgsky, Steve Reich, and Jean-Claude Risset to name a few – have played with relationships between speech and music, either by composing music that has some of the qualities of speech, or by embedding short segments of speech in musical contexts.

In particular, Mussorgsky has argued that music and speech are in essence so similar that with practice a composer could even reproduce a conversation in music. As he wrote in a letter to Rimsky-Korsakoff: ‘whatever speech I hear, no matter who is speaking…my brain immediately sets to working out a musical exposition for this speech’.

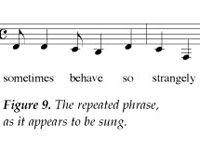

In our final demonstration, speech is made to be heard as song, and this is achieved without transforming the sounds in any way, or by adding any musical context, but simply by repeating a phrase several times over. The demonstration is based on a sentence at the beginning of the CD Musical Illusions and Paradoxes. When you listen to this sentence in the usual way, it appears to be spoken normally — as indeed it is. However, when you play the phrase that is embedded in it: ‘sometimes behave so strangely’ over and over again, a curious thing happens. At some point, instead of appearing to be spoken, the words appear to be sung, rather as in the figure below.

After listening to the repeated phrase, listen to the full sentence again. You might find that it begins by sounding like normal speech, just as before, but that when you come to the phrase that had earlier been repeated: ‘sometimes behave so strangely’, the words again appear to be sung.

So I leave you with a conundrum: Why should the simple repetition of a phrase, without any change at all, cause our perception to shift so dramatically from speech to song?

This Radiolab story features the LaGuardia High School Chorus and Robert Apostle. The series is produced for NY Public Radio, distributed by NPR, and supported by National Science Foundation and The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Walt Boyer’s fifth grade music class, Atwater School, Shorewood, Wisconsin:

First track on John Somebody:

“John Somebody” had its beginning in tape loops of speech, laughter, and crying that I made in the late 1970’s. From my source tapes, some made by simply recording one side of a telephone conversation, I chose short fragments that evoked the rhythms of dance music and rock songs, and wrote down the approximate pitches of the words. Longer melodic lines were created by editing phrases and even individual notes together: the twelve bar melody of Involuntary Song 3 required a 25 foot tape loop (quarter note = 2 5/8 inches). The instrumental score is based on the pitches and rhythms of the recorded voices, and the initial connection to popular music is seconded by the orchestration: opening with all electric guitars, and later adding percussion and winds.

To my knowledge, John Somebody was the first piece to use the transcribed pitches and rhythms of a recorded speaking voice as the basis for an instrumental score. The technique is based on a simple observation: although the pitches of speech are rarely stable or exact, when they are placed against a tonal center, the ear will tend to interpret a phrase as being in a mode or key. Similarly, repeated syllables resolve into a rhythm more regular than reality. Instrumental doubling and support creates a strong sense that the speech is in time and in tune. But when surrounded by instrumental doubling and support, the power of suggestion will create a strong sense that the approximate rhythms and pitches of the speech are in time and in tune.

Precedents abound: call and response is nearly universal in musical traditions worldwide: I was particularly aware of blues, and Messiaen’s transcribed bird songs as well. And as affordable tape recorders became common in the second half of the 20th century, speech joined myriad bangs, scrapes, and whooshes as a favorite subject for tape pieces. But with John Somebody, recorded speech became both source material and accompaniment for instrumental writing, a technique that spread as digital sampling became common in the mid-1980’s.

The first four phrases heard at the beginning of Part I, which soon sprout rock power chords and guitar lines, are the very phrases that gave me this idea, and the first that I sketched out musically in 1977, before putting them aside for other projects. Two years later I picked up these sketches and began edit, mix, and write. Soon I performed an early version of Part I in a 1979 concert at post-punk palace The Mudd Club, organized by the experimental arts center The Kitchen. Although about half of the core materials for John Somebody came in to being between 1977-79, I date this piece 1980-82, when the partially developed elements laid out on my table met the animating idea of the Baroque dance suite. This became a model for me: music that is episodic but unified.

The original phrases were looped and layered in synchronization on a multi-track tape machine. Then that polyphonic tape was itself looped, and the results carved into with a mixing board, which allowed me highlight any segment of any phrase, or combine it with others, all in pre-arranged rhythmic synchronization. I had recently invented this technique with four-channel loops of my own laughing, crying, and coughing, in a never-quite-satisfactory project called Involuntary Songs — its best section became the underpinnings for John Somebody’s Involuntary Song #4. Part I of John Somebody grew from my original four phrases; I began Part II by editing out every use of the word “think†on a recording of my own phone conversation, and Involuntary Songs 1-3 came from a tape of a girlfriend laughing…

—Scott Johnson, Notes on the Music

Toronto composer Adam Goddard celebrates of the life and character of his 90-year-old grandfather, Henry Robert Tindale Haws, a farmer in rural Ontario — turning an interview into music. “More About Henry” with Steve Wadhams as part of their one-hour feature, “The Change in Farming,” for CBC Ideas (PRX version: “The Change In Farming“).

The music of preachers, excerpted from a ninety-minute experimental theater piece using sound collage, slide projection, and choreopoetry; adapted for radio. Included on Tellus #11: The Sound of Radio:

Off the self-titled Lecture On Nothing, aka, producer Eddie Miller.

Sampling a broadcast sermon by Reverend Paul Morton, New Orleans, June 1980; off My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Wanna try making your own version? Byrne and Eno offer all the original multitracks of thise and one other composition for you to download & remix.

“Mrs. Morris (Reprise)” (2009 / 2:57) Charles Spearin

From The Happiness Project by Charles Spearin (multi-instrumentalist, founding member of Broken Social Scene and other bands, now touring with Feist):

These are my neighbours. My wife and I have two little kids and live in a multi-cultural neighbourhood in downtown Toronto. In the hot summer months all the kids in the neighbourhood play outside together and everyone is out on their porch enjoying each other’s company, telling stories and sharing thoughts. A year or so ago I began inviting some of them over to the house for a casual interview vaguely centered around the subject of happiness. In some cases we never broached the subject directly but none-the-less my friends began to call it my “Happiness Projectâ€.

After each interview I would listen back to the recording for moments that were interesting in both meaning and melody. By meaning I mean the thoughts expressed, by melody I mean the cadence and inflection that give the voice a sing-song quality. It has always been interesting to me how we use sounds to convey concepts. Normally, we don’t pay any attention to the movement of our lips and tounge, and the rising and falling of our voices as we toss our thoughts back and forth to each other. We just talk and listen. The only time we pay attention to these qualities is in song. (Just as when we read we don’t pay attention to the curl and swing of the letters as though they were little drawings.)

Meaning seems to be our hunger but we should still try to taste our food. I wanted to see if I could blur the line between speaking and singing – life and art? – and write music based on these accidental melodies. So I had some musician friends play, as close as they could, these neighbourhood melodies on different instruments (Mrs. Morris on the tenor saxophone, Marisa on the harp, my daughter Ondine on the violin, etc.) and then I arranged them as though they were songs.

All of the melodies on this album are the melodies of every day life.

—The Happiness Project by Charles Spearin